Consent is an agreement between two people about how to move forward in a sexual relationship. While one might assume that obtaining consent is easy, American society has never created a space for people to learn how to obtain consent. What appears to be a simple issue of “yes” and “no” to sex often turns into “he said, she said” when someone makes an accusation of sexual assault.

So how do we improve our knowledge of how to handle consent? The sex positive community has not been a good example. In 2018, a well-known sex educator was accused of sexual harassment by a colleague. Though he later apologized and entered into a restorative justice process with other colleagues, his initial decision to not take responsibility showed a huge gap between his preaching about obtaining consent versus his actions.

He had created a well-known model for consent, a way to establish boundaries and agreements before sexual activity. If a person who taught others how to obtain consent made a potential partner feel pressured, how can a regular person know what to do when consent gets messy?

I decided to develop my own model for consent. Who am I? I’m the website editor of Black & Poly, a community for black people transitioning to polyamory. I have been an assistant organizer for my local polyamory group and I am part of the sex-positive New Culture movement. I’ve taught others about consent and I am a survivor of sexual abuse. I identify as a womanist and I believe everyone wants to get this right.

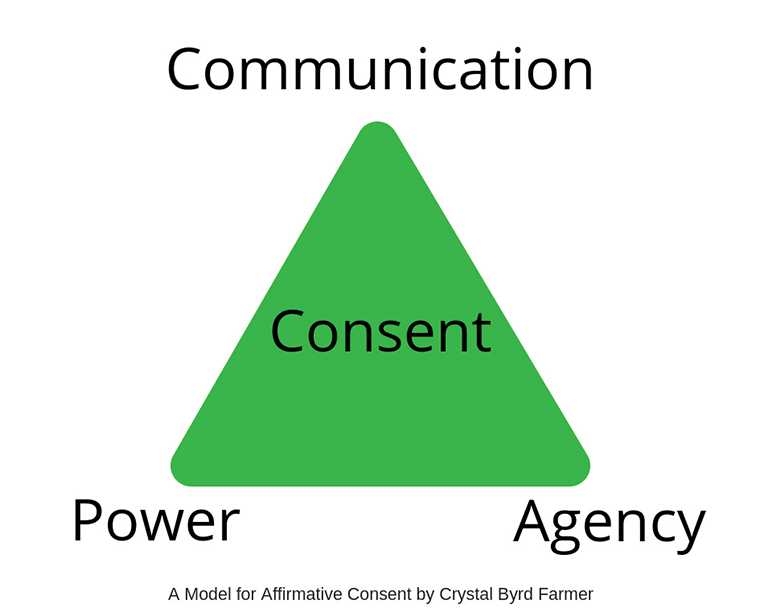

This consent model goes beyond the basics of who, what, and how. It starts with the recognition of agency and power balances and ends with specific communication about sexual acts. This model has the form of a triangle in equal relationship to each other. If one part is missing or abbreviated, it will affect the entire experience of giving and obtaining consent. Here are the three legs: agency, power, and communication. I’ll break down each leg in detail.

Agency

The first leg is agency, which is the recognition that we all have the ability to make choices for ourselves. We make those choices based on available information and our own judgment. When we’re in a relationship, disclosing relevant information is the way we recognize our partner’s agency.

For instance, a person in the dating scene may tell a potential partner that they are seeing others. For those currently in a relationship, it may mean telling a partner that they have acquired an STI. This information usually affects the partner’s future actions, which is why it’s difficult and sometimes embarrassing to talk about. When we withhold information, we are taking away some of our partner’s agency. When a partner has the right information, they can respond in a way that will protect their own safety and peace of mind.

Another part of agency is cognition, or each person’s ability to understand the situation. Children, teenagers, and even young adults do not have the brain development of mature adults; it’s why we restrict drugs, alcohol, and driving by age. In the same way, neurodiverse people often lack the social awareness that will give them the information needed to give or obtain consent. For all people, impairment due to drugs and alcohol means people may make different decisions than if they were sober.

When determining if your partner has agency, compare their individual abilities against what is expected of people the same age and disability status. If they are under the influence of drugs or alcohol, are they cognizant of the decision they are making and its possible effects? Recognizing our partner’s agency is a critical part of obtaining consent. We must also acknowledge that even when consent is asked for and given, actions could cross legal and/or moral boundaries.

Power

The second leg of the consent triangle is the awareness of power. It’s no accident that the majority of celebrities called out for sexual assault and harassment in the #MeToo movement have been powerful white men. Men born in the US have been brought up in a culture of toxic masculinity that values aggressiveness, manipulation, and dishonesty in order to “get the girl.” When a potential partner refuses to consent, a man’s response of disappointment and even anger is seen as socially appropriate.

Men are not always the bad guys, though. Any relationship between two people is subject to a power imbalance when someone has more seniority, wealth, status, or social support than their partner. Women who pressure men into sex by using their “feminine wiles” are just as guilty of manipulation. The power dynamics of each relationship is not fixed, and it’s always subjective. If someone believes they have less power, that will impact their ability to deny consent.

Before engaging in sexual activity, people should acknowledge the power they hold in the situation. Have they considered the reasons their partner might say yes besides an actual desire to engage? Are they using their position or cultural privilege to get their desired outcome? Can they give their partner the space to say no without fearing the consequences?

The fear of rejection is a powerful motivator during consent conversations. Saying or hearing “no” can be painful no matter how justified it is. In fact, many people go through with sex they are not sure about because the idea of hurting their partner seems to be worse than grinning and bearing it. To counter this, sex educators have asked people to ask for enthusiastic consent: it’s either a “Hell, yes!” or it’s a “no.”

Consent is almost meaningless when one partner has created a power imbalance through coercion and violence. People evaluating consent from the outside cannot use someone’s failure to stand up to or leave their abuser as a sign of consent. In the same way, it can be difficult to tell if a situation is sexual harassment or not. We can only start by believing the accuser and looking for patterns in each person’s behavior as it relates to the power balance.

Communication

The final leg of consent is the actual communication. Even in romantic comedies where the couple is falling over each other to get in a bed, consent has to be asked for and given. In an ideal world, progressively more intimate activities are verbally consented to by each partner. In the real world, it looks more like shy touches, smiles, and other nonverbal communication. The problem is that some people will look back on those activities and know that at some point they were unwilling to continue.

The moment bad sex becomes something worse is when this unwillingness is glossed over, when one partner notices that something is wrong but continues anyway. We have all experienced the feeling of powerlessness when we give up our agency to another. Our consent is half-hearted, and the guilt can be overwhelming. If you’ve ever had that experience in a non-sexual situation, then try to act with compassion when you see your partner hesitating to give consent.

So what does a conversation about sex look like? It starts with the truth. “I want to be intimate with you.” Even if the phrase sounds awkward and perhaps unauthentic, I encourage you to go into even more detail. The initial yes should be followed up with a checklist of sorts to cover the entire spectrum of sexual activity. Consider the following areas:

- Dirty talk

- Kissing

- Touching genitalia and erogenous zones

- Penetration (genitals, fingers, toys)

- Oral sex

- Anal sex

- BDSM activities such as spanking and fetishes

In the spirit of recognizing agency, both partners should discuss any potential barriers to consensual sex. This includes:

- STIs and date of last testing

- Use of barriers (such as condoms or dental dams), what kind and where

- Current relationships and agreements

- Past sexual history

- Use of birth control or medical sterilization

- Medical conditions and other physical limitations

- Psychological limitations, history of abuse, and triggers

- Attitude towards sex and how it will affect the relationship moving forward

Practice communicating consent before you and your partner get to the bedroom. Over time, these conversations will become commonplace and easier. It’s understandable that not everyone can talk about these things without feeling embarrassed or nervous, but sex is not something to be done in the proverbial dark. The more openness you bring to the conversation, the less shame you will feel around one of the most human of activities.

At the end of the day, consent is just one part of navigating relationships. Due to the legal and social change in the world, it’s more important than ever to find a way to give and obtain consent without shame and guilt. Recognizing each other’s agency, addressing power imbalances, and communicating consent is a great way to create space for the pleasurable experience that sex should be.

This article is adapted from a version that appears at blackandpoly.org/the-triangle-of-consent.

Crystal Farmer is an engineer turned educator from North Carolina. She became the organizer for Charlotte Cohousing in 2016 and has been involved in cohousing and the intentional communities movement ever since. She is passionate about encouraging people to change their perspectives on diversity, relationships, and the world. She owns Big Sister Team Building and teaches at Gastonia Freedom School, an Agile Learning Center. She is also a member of the FIC’s Editorial Review Board. Her article “Barriers to Diversity in Community” appeared in Communities #178.

Excerpted from the Summer 2019 edition of Communities (#183), “Sexual Politics.”