By Melanie Rios

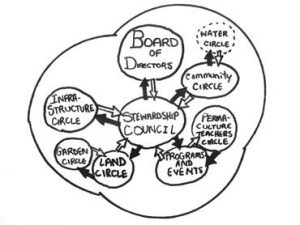

Partial diagram of sociocratic organizational structure at Lost Valley Center. The water circle was a temporary circle that has since disbanded. The arrows stand for people who are representatives of one circle to the other circle.

In 2008 Lost Valley took decision-making power away from its consensus-based intentional community and transformed into a hierarchical business. The organization (a 501(c)3 nonprofit operating an 87-acre permaculture education and conference center outside Dexter, Oregon) hoped to become more economically solvent through this change, but it continued to struggle financially.

Two years later, in dire economic straits, we began integrating top-down and flat-hierarchical governance systems by adopting a system called sociocracy, which I learned about at a workshop by John Schinnerer at the Northwest Permaculture Convergence. Here is how our conversion to a sociocratic governance system at Lost Valley can be viewed as a form of social permaculture that has helped our 21-year-old community thrive both socially and economically.

Observe First, then Interpret and Interact

The first principle of permaculture is observation. In the visible world, for example, we are advised to observe flows of water and other characteristics of a newly acquired property for a full year before taking steps to change what is there. I have been observing Lost Valley for a decade, first as a visitor and a student, then as a guest permaculture teacher, and now in the role of Executive Director. I see the succession of governance systems at Lost Valley as a natural progression from what the spiral dynamics folk call the green vmeme to the yellow vmeme.

The Lost Valley that I first entered 10 years ago came straight out of the green vmeme. The community valued cooperation over competition, process over product, equality in decision-making, and expressions of affection more than economic profit. There were many wonderful aspects to this way of being. Hugs and empathy were plentiful, and folks knew how to talk about and support each other having feelings. People felt included and empowered to participate in making decisions that affected them. Lost Valley folk lived simply and frugally while helping our planet and living in close connection with each other.

But there were shadow sides to this way of being. Long meetings with few decisions eventually discouraged members with initiative from pursuing their dreams at Lost Valley. The whole group often had difficulty achieving consensus on a given proposal, and so individuals who wanted to accomplish things in the world moved away. Others left because decisions were mediocre; someone who knew nothing about fire safety would have as much power to make a decision on that topic as someone who was an expert. These departures of high-powered, competent members contributed to economic stagnation. The community was barely scraping by, with mounting deferred maintenance on buildings and a high turnover of community members.

About three years ago, Lost Valley made a transition intended to call in the yellow vmeme values of effectiveness, ease, and excellence. A few folks stood up at a meeting and said they were all leaving the community if the consensus-based governance structure weren’t changed to give more power to those who were more competent and responsibly engaged in supporting the business side of the community. After discussion, the community agreed to the changes they proposed, and a newly invigorated nonprofit board of directors assumed leadership of the community, creating a hierarchical structure of governance. The board hired an executive director and managers to accomplish the work of Lost Valley’s nonprofit organization, including hosting permaculture educational programs and conferences.

I enjoyed many of the changes that came out of this transition. Staff meetings were less likely to be derailed by a long detour into exploring someone’s feelings. The organization established systems of accountability and defined tasks and roles, while staff management learned how to write and follow budgets. These changes set the stage for moving the community forward.

But there were shadow sides to this transition, taking the community on a detour back to the orange vmeme, which values hierarchical decision-making, product over process, and profit over heart-centered goals. Volunteers and staff were afraid of speaking truthfully to those above them in the hierarchy for fear of being asked to leave. Managers made autonomous decisions without the input or knowledge of those who were affected by these decisions, and gossip and resentments ran rampant. Community morale was low, which negatively affected the experience of our students in addition to those who lived here. In September 2010 word arrived from the chairman of the board that the community would run out of funds in December, and that unlike other similar challenging moments in previous years, no one had energy or ideas for borrowing funds to make it through the winter.

Upon hearing this news, I thought of the many people who have enjoyed and contributed to Lost Valley’s land and mission, and the many more who would like to do so. I felt sad to think that our planet’s ecological movement might lose the zoning of this land, which allows us to live collectively, to host educational programs and conferences, and even to build more homes in an ecovillage cluster rather than on a grid. Saving Lost Valley as a nonprofit dedicated to environmental education felt like a project that was both doable and sufficiently challenging to be of interest. So I stepped up to invest funds and other forms of energy to help keep Lost Valley alive, and I invited others to join me in this project. Our challenge was to figure out what we could do to help Lost Valley finally make the transition to the yellow vmeme, a place of both joy and effectiveness.

Small and Slow Solutions

The permaculture principle “use small and slow solutions” helped us at this stage. Applied to our homesteads, for example, this principle suggests that we make changes to our land starting at our doorstep, and only slowly implement more sustainable elements of our design as time and funds allow. I saw that Lost Valley was a microcosm containing the world’s challenges, and that I may or may not be able to help solve these problems. Wisdom from an Eckert Tolle book steadied me for the journey ahead: “Whatever is born of stillness, the outcome will be good.” It wouldn’t do any good to give up my meditation practice and run around exuding anxiety about the dire straits we were in. I could move slowly, one step at a time, practicing non-attachment to outcome, finding satisfaction in simply doing my best.

Out of this awareness, a “Positive Action Team” was born at Lost Valley. The seven members of this team were folks I felt closest to at the time, and we began by each choosing one small action to implement unilaterally at Lost Valley. One person decided to tell folks she met during the course of her day what she appreciated about them. Another chose to clean up messes he didn’t make. Another decided to build beautiful altars out of natural objects. These individual small actions had a rapid effect on morale at Lost Valley. We felt more connected and hopeful within the first week of beginning this experiment, and within two weeks it appeared that others who weren’t yet part of us were feeling better as well.

Our next step was to study and practice sociocracy, a governance system based on a pattern of inter-linked decision-making circles that each contains a small number of people. Meeting together in small groups is more engaging than larger ones because there is more space for each participant to actively participate in the conversational flow. And small groups of five to 10 members are more effective than larger ones at making good decisions quickly.

The Positive Action Team became the first sociocratic circle at Lost Valley, and it would later give birth to other circles above and below it in the governance hierarchy before finally disbanding. Rather than have circles expand to include lots of new members, a new sociocratic circle arises when an existing circle elects a representative to start another circle with a mission to focus on a defined aspect of the organization. That representative becomes the voice of the original group to the new group, and selects people to serve on the new group. The new group then elects a representative to the original group. The circles thus become “double-linked,” as shown in the diagram of Lost Valley’s current governance structure.

For example, Colin, our representative from the stewardship circle to the community circle, shares decisions that the stewardship circle has made that impact the community. Justin, elected to represent the community circle on the stewardship circle, keeps the stewardship circle informed about what’s happening in the community, and advocates on the community’s behalf. This allows information to flow both ways in the hierarchy of circles, with folks in the lower circles sending information about proposals and decisions to the circles above, and vice versa.

Apply Self-Regulation and Accept Feedback

These double-linked circles facilitate the feedback referred to in the permaculture principle “apply self-regulation and accept feedback.” An example of this principle in the visible world is placing electric meters at the entrance to one’s house, rather than behind some bushes in an obscure corner outside the house. That way residents can see how much power is being used as they leave home, and respond to this feedback by regulating how many appliances they leave plugged in.

A sociocratic example of this flow of feedback was when someone informed the community circle that some people were getting ill, and they thought it might be due to problems with our well water. The community circle formed a temporary circle called the “water circle,” tasked with researching the issue and coming up with a proposed solution. The water circle reported back their suggested course of action to the community circle, who liked it enough to refer it up to the stewardship circle, who liked it enough to refer it up to the Board of Directors. The folks in the water circle presented their ideas in each of these circles, and in the space of just a few weeks, the Board approved their suggestions for funding.

The “apply self-regulation and accept feedback” principle benefits from transparency, one of sociocracy’s core values. Sociocratic governance calls for open, honest communication about everything from financial books to feelings people hold about each other. With this value in mind, I met with the chairman of the board when the Positive Action Team was just starting up to request access to economic information about Lost Valley so that we could make informed backup plans in case Lost Valley ran out of funds.

Sociocracy also encourages groups to apply self-regulation and accept feedback by requiring three steps of those charged with accomplishing tasks: planning, implementation, and evaluation. Before electing someone to do something, the circle clearly defines the nature of the task, establishes a timetable, and creates a plan for evaluating the results. Sociocratic circles consist of folks with expertise and/or strong stakes in the task at hand, and they receive creative latitude to accomplish their task as they deem best without being micromanaged by the circle above them in the hierarchy. The higher circle can intervene, however, if the circle charged with a task goes sufficiently off track or doesn’t get the job done on schedule. When tasks or meetings are finished, we take time to evaluate both the process and product so that the group can learn to do things better in the future.

Sociocratic elections encourage people to give positive feedback to each other by asking members of circles to talk openly about why they want to elect someone for a task. The Positive Action Team employed a sociocratic election to create a financial circle charged with learning about the economic situation at Lost Valley. To elect the Positive Action Team’s representative to this financial circle, we passed around slips of paper upon which each person wrote their name and the name of the person they wanted to head up this new circle. Then a facilitator asked each person why they nominated the person they chose. During a second go-round, people were allowed to change their nominations based on the reasons they had heard from others. The facilitator then suggested someone to head up the circle based not strictly on the number of nominations, but rather on the strength of the reasons, and asked each person whether they had any “reasoned and paramount objections” to this suggested person. In other words, a person would have to have a good and strong reason to block someone’s election, not simply that he or she would prefer someone else. Once someone is elected, he or she is asked if they want to accept the job.

This sociocratic nominating method resembles the consensus decision-making process, but the wording “Do you have any reasoned or paramount objections?” encourages even untrained people to use a block well. If someone does have an objection, or if the person who is elected doesn’t want to serve, then the facilitator suggests someone else. We’ve found in practice that objections have been rare and fairly easy to respond to, and that almost everyone who is asked to serve chooses to do so. The mood of a group after elections is often one of connection and trust because we’ve taken time to tell each other why we love and respect each other. The person who is charged with creating a new circle and executing the assigned tasks knows he or she is supported by the group, and can act with well-earned authority. In this way, sociocracy is both participatory, in that each person in a circle has an equal voice in selecting someone to do the work, and effective, in that those who are selected to do the work are given the power to act.

Creatively Use and Respond to Change

This permaculture principle keeps us light on our feet, looking for the good in even challenging situations. The local and organic food movements, for example, are creative responses to the toxicity and increasing expense of using petroleum products for growing food. Sociocracy is also known by another name, dynamic governance, because it is especially useful in times of rapid change. In the year since we formed our first sociocratic circle at Lost Valley, much has improved here in our morale, our facilities, and our quality of life. From a community that had dwindled to just a handful of folks over the winter, we now have 40 people living here and a couple of new businesses to provide employment for them. We’ve renovated many buildings, cleaned and de-cluttered everywhere else, and upgraded our water systems. Several households plan to build their own homes on the land, so that we will no longer be a community exclusively of renters. Our cash flow has been positive since the beginning of this year, even through the winter when Lost Valley has typically lost money. I feel grateful for the sociocratic governance methods that have facilitated this joyful and effective progress.

Excerpted from the Winter 2011 edition of Communities (#153), “Permaculture.”