By Jeff Golden

Let it not surprise you my friends, when I say, that the spot on which we stand has never been purchased or rightly obtained; and that by justice, human and divine, it is the property now of the remnant of that great people, from whom I am descended. They left it in the tortures of starvation and to improve their miserable existence; but as a cession was never made, their title has never been extinguished.

—Mohican Chief Quinney

from a speech delivered the 4th of July, 1854, in New York

For the 98 percent of us in the United States who are not Native American, what does it mean to live in this country today, to live in the shadow of what was done to the native people? What does it mean to be living on and trading in land and resources that were taken from the native people through intense and chronic violence and deceit?

The Common Fire Housing Co-op was created in 2005 in New York’s Hudson Valley with a vision of providing a home for people who wish to be very intentional about living in a just and sustainable way. One of the four core principles was Aligning Our Lives with Our Beliefs. We shared a sense that much of the violence and destruction in the world today arises not from malice, but from people being invested in the current systems and contributing to them in small ways that add up and give the systems power. And so we sought to think and act together to try to weave greater integrity into our everyday lives and into our work and service in the world.

That showed up in a number of ways, many of which will not be new to other community-minded people. Community members were selected specifically with an eye to their commitment to making a difference in the world, in whatever ways that showed up in their lives. The building that housed the co-op was built to be extremely environmentally-responsible, and earned the first Platinum certification in New York from the US Green Building Council. The food that residents bought and prepared together was primarily local and organic. Residents organized and participated in regular trainings on important issues and critical skills related to living in community and being effective in the world. And so on.

We also sought to grapple with those fundamental questions about the history of the land and the people who once lived there, and what was done to them and what became of them.

To do that, it was first necessary to find out just what that history was, and even who those people were. Asking other locals about it revealed that most people had no idea what tribe had lived in that area, and the town’s website and the few individuals who did offer answers turned out to all be wrong. None of the basic histories of New York or of the local area had any solid information, so the residents had to dig deeper into histories and primary materials specifically focused on Native Americans.

The History and the People

But the history and the people did reveal themselves with some persistence. The first people arrived in what is today known as New York’s Hudson Valley some 12,000 years ago. Their descendants lived in the area for about 600 generations before the first Europeans (led by Henry Hudson) arrived in 1609. At that time the Mohicans lived where the housing co-op would be built nearly 400 years, or about 20 generations, later. And it turns out the story of their interactions with the Europeans is as grim in its own way as any tale told by other native people in America.

A huge percentage of the Mohicans died from diseases that came with the Europeans. Another large number of them died from violence with other Indians that escalated with the arrival of guns and trade with the Europeans. And a large number of them were intentionally killed by Europeans. Those who survived were forced from their land and driven away. The pre-contact population of the Mohicans is unknown, but was somewhere between 5,000 and 12,000. Within a mere 50 years that had dropped to less than a thousand, and there were virtually none left in the Hudson Valley.

Some 50 Mohicans took refuge at a Protestant mission near the border with Connecticut where the missionaries were very helpful, exposing traders who illegally sold the Mohicans alcohol, and offering legal support in their dealings with the Europeans. The local settlers spread rumors of atrocities committed by the Indians, they prevented people from visiting or trading with the mission, and they eventually petitioned the governor for permission to kill the Indians at the mission. The petition was denied, but it sufficed to drive away the remaining Mohicans in 1746.

Many of the survivors found their way to western Massachusetts and tried to survive by adopting the customs and occupations of the Europeans. In the 1780s they were forced to relocate to western/upstate New York with the Oneida tribe. In 1818 they were in turn driven from that land to Indiana. And in 1822 they were forced to Wisconsin. The 40,000 acres they were given there was reduced to 16,000. The land was not generally suitable for farming, so much of it was turned over to logging companies who clearcut the land. With very little food or shelter, some of the Mohicans moved into the abandoned offices left by the logging company. Many of their children were sent to boarding schools run by non-natives that forbade the kids from speaking their native language and practicing their native customs. Their population at one point fell to 600.

Contrary to what James Fennimore Cooper might have had us believe, however, with his fictional book, The Last of the Mohicans, the Mohicans did survive.

A large number of their descendants—some 750 out of about 1500 enrolled tribal members today—live on that same reservation today. The forests have returned, along with the wildlife; housing has expanded greatly; there is a health center, a meeting hall, and more. The largest employer in the county is a tribal casino, which generates a large degree of the income on the reservation. In the words of one Mohican, Molly Miller, “The road from colonization is long and painful but we continue to work at it.”

What To Do?

Which brings us back to those initial questions. What does it mean to “own” a portion of this land that was so violently taken from those people who had lived there for 600 generations? What does it mean to live on that land, to enjoy it and so many of the benefits and riches that have flowed from these lands, benefits and riches largely denied to the children and grandchildren of those people? And what does it mean to go about our daily lives in a larger community and society while this massive violence and injustice is largely ignored, unacknowledged, and even unknown by so many, and on some levels continues to be perpetuated against those people?

For those of us in the co-op, it meant writing up and sharing publicly what we had learned about the Mohicans, as well as what we learned about other aspects of the history of the area, including a significant use and abuse of black slaves, and sharing that history with all who visited the co-op, and making it available on our website.

It meant creating an initial pool of money. Without knowing for sure what we were going to end up doing or what kinds of resources we would need, everyone in the co-op agreed to pay an extra $10 a month towards the “Mohican Project.”

It meant reaching out to a number of Mohicans both in New York and on the reservation to discuss with them what they thought the residents could or should do. Once again, a little legwork was required. Who to reach out to? And how? We read through the tribe’s website and found that they have a couple committees that felt related to our efforts and concerns. One is the Historical Committee, the other the Language and Culture Committee. (The last fluent speaker of Mohican died in 1933, and many aspects of the traditional culture were intentionally stamped out by the Europeans, so nurturing the cultural and linguistic roots of the Mohican people, in a sense the spiritual roots of the people, is an important focus for some in the tribe.) So we wrote to those committees.

We also read the tribe’s biweekly newspaper online and subscribed to it. There we gleaned a few other names of people who seemed like good contacts for us—one who writes a regular history column; another, apparently the only enrolled tribal member located in the Mohican homeland, who was a Masters student in history; some people involved in the local museum.

We wrote these people, sharing a little about who we were, and seeking whatever thoughts they might have about ways we could help to heal this history and take responsibility for the legacy we had inherited. Some people we never heard back from. Some very kindly referred us to other people. And a couple of them fully engaged us, sharing deeply of their own experiences and suggestions, and reaching out to other tribal members for their own thoughts.

The history of what had been done to the Mohicans and what had become of them was obviously well-known to those people, but the questions we were asking were generally new to them; they hadn’t been asked them before. The 400-year anniversary of Henry Hudson’s arrival in this area was about to be commemorated a year later and some of their initial ideas included providing a place for people to stay if they were able to organize a trip back to their homeland for that, supporting them doing some kind of “wiping of the tears” ceremony, and helping them with their land claims, as well as continuing to educate locals about their history and who they are today. They were all very supportive of what we were doing as a co-op, both in relation to the Mohicans and in general, though one person courageously added, “To be really true to your thinking, if there comes a time that the co-op were to be no longer, then will your land back to the tribe.”

We had the Mohican who lives in New York come and speak at one of the annual Harvest Festivals held at the co-op. We tried to get the local town to correct its website to acknowledge who the real native people were in that area and what became of them, though there was some defensiveness and uncertainty about whether what we had discovered was true, and the website never was changed. There are a couple “Welcome to Red Hook” signs at the edge of town. We also requested that the town add to those signs, “The Southern Boundary of the Mohican Homeland.” That required going through one of the local clubs, and we didn’t get too far with that. We also considered trying to get some information about the Mohicans in the local school curriculum, but the process for that seemed very daunting.

One of the co-op residents helped us really focus our intentions by posing the simple but powerful question: “Today almost nobody knows who the native people were here. What do we need to do to make sure that a generation from now almost everybody does?”

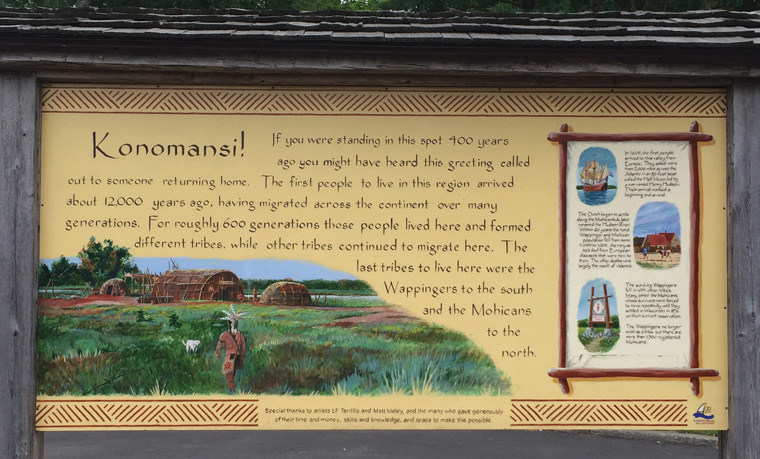

We decided to focus our efforts on getting a mural erected somewhere very visible in town, but on private property, where we really would only need to deal with one person, the owner. Using images of Mohicans from a painter in the region who seemed to have an informed and not stereotype-based or derogatory sense of the Mohicans, we created a draft of what the mural might look like, including some of the history and some key images. We scouted possible locations and decided that the most popular ice cream shop in the county was hands down the best place to really get our images and information before a lot of people, and in a positive, familiar environment.

We asked around about the owner and were told by one person that there was zero chance, that he was politically not at all the kind of person who would support us. But we reached out to a couple prominent people in town with whom we had relationships and who were of the same political party/perspective as the owner of that land, and they helped us connect with him. We sent him our request along with the draft image. We had a meeting on-site and found him to be really supportive of the idea. We discussed the location and he ran it by some of the store owners in the plaza there. He asked for just a couple changes to the language and gave us a green light.

We then took the images and text to our main contacts among the Mohicans for their feedback. Again, with a couple minor but meaningful changes they felt good about it as well.

We got in touch with a prominent muralist in the region who advised us on what kind of wood, paint, and finish to use. We got someone to project the image and paint it for us on a piece of 4’x8′ high quality plywood. Another person donated some rustic posts; other people donated the labor of putting them in the ground and erecting the mural. Using our pool of money and fundraising from locals and friends and family, we raised the $1,000 that the mural ended up costing us on top of the volunteer labor and donations. And we created a companion website to the mural, sharing what we had ourselves learned about the Mohicans. You can see that at www.redhooknatives.org.

The mural turned out beautifully, and it is seen by so many people!!! We couldn’t be happier with that part of our journey.

The End of the Co-op

For a variety of reasons, in 2013 we decided to close down the housing co-op. The question of how to be in right relationship with the Mohicans through that process was important to us. We owed a lot of money on the building in the form of a mortgage with a local credit union, so we couldn’t just “will the land back to the tribe,” as that one Mohican had suggested. But we were willing to sell the land to the Mohicans for the rock bottom amount of money we needed to cover that mortgage. And we reached out to some friends who are native and very active in their communities, and we discovered that there are a couple organizations that donate money and offer loans in support of native people regaining access to their original land.

We wrote the person who was our main contact on the reservation about what we were thinking, and about those two organizations, and about our willingness to do our best to help with fundraising as well through our own networks. Our contact forwarded our letter to the tribal government for them to consider. We weren’t sure how important taking ownership of this land would be to the Mohicans, or whether they would feel it was worth whatever effort or money it would take to pull off this purchase. But we never heard back from them one way or the other, even after following-up a couple times.

So we did what felt to us like the next best thing. We sold the property and committed to in some way investing any money left over to supporting the Mohicans. We took the responsibility of shepherding that money very seriously. Tribal governments are often not particularly effective. We did not have any reason to believe that was true in the case of the Mohicans, but by that time our relationship with our main Mohican contact had deepened, a couple of us had actually met her and visited the reservation in Wisconsin, and so we had a lot of trust in her and felt very good about her helping guide us in terms of how to direct that money.

So far we have donated $28,000, with a little bit of money still tied up in legalities around the property that will hopefully be freed up at some point for us to add to this amount, though that is uncertain. The money has been donated to the Historical Committee, which is part of but has separate finances from the general tribal government. The money has been used to support a gathering of native people on the Mohican reservation, a gathering of native people near the Mohican homeland, and efforts to reconnect with the Mohican language.

In the letter we wrote that accompanied our last donation, we wrote:

“It’s a strange and cruel thing that we have had the opportunity to live in the Mohican homeland, to enjoy many of the blessings of this land, and to have even ‘owned’ some of this land by the laws and customs of the United States, knowing full well that these laws and these opportunities rest on a foundation of profound violence, disrespect, and oppression that killed and drove off the Mohicans and other native peoples who had lived here for thousands upon thousands of years.

“We are clear that we are returning a very tiny portion of so much that is rightfully the tribe’s to begin with—riches that were stolen long ago. This is not a gift or donation from us to you, it is that tiny portion finally finding its way back to its proper place.

“It is our hope that this money and the spirit in which we offer it help to bring greater joy, peace, and health to some in the Mohican community.”

In that same vein, I offer this article, not because I think we got everything “right” or others need to do exactly what we did, but in the hope that it is helpful and inspiring to you on some level, and does help to feed greater joy, peace, and health in relation to the native people of these lands.

Jeff Golden cofounded Common Fire and played a central role and lived in its two communities in New York’s Hudson Valley, including the Common Fire Housing Co-op in Tivoli. More recently, he contributed the article“Common Fire’s Top Ten Hard-Earned Tips for Community Success” to Communities #170.

Excerpted from the Fall 2016 edition of Communities (#172), “Service and Activism.”