By Peter Moore

Right up front, I confess I am a bit of a scofflaw at heart. If I can do it myself, I’d rather do it in a good way that makes sense in the situation than have to apply some one-size-fits-all solution to a unique situation. And living in community is unique, to be sure; anyone who does knows what I am talking about.

In 1968, as a student at San Francisco State College, I came to know a local guru named Stephen Gaskin. He offered a thing called “Monday Night Class” in his living room in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood, near where I lived. This was at the height of the Hippie era, with hundreds of communes, cults, and conspiracies flowering in the City. It was at one of his talks where he said (in essence): when you live around dinosaurs, and you know they’re existentially unsustainable, your best survival strategy is to neither fight with them nor live under them. Why? If you fight a giant, cold-blooded body that’s bigger than you with lots of teeth, you don’t stand a chance. And when that unsustainable body inevitably falls, you don’t want to be under it, for obvious reasons. Better to just do your own thing, live your life by your terms, and not attract too much attention.

It was a useful metaphor for countercultural colleagues collaborating on a collective vision beyond normative institutions of the day, during that particular Age of Aquarius (think War on Drugs, the Draft, Viet Nam, Sexual Revolution, Civil Rights Movement, Women’s Liberation, Stonewall, Kent State, City and Country Communes, etc.). Stephen eventually led an exodus of a hundred hippie vehicles, out of the City on an odyssey, all the way from the coast of California to establishment of The Farm in Tennessee. This became a truly successful intentional community that lived by its own rules while maintaining relationships with “authorities” on an as-needed and need-to-know basis.

So what is authority? For the purposes of this essay, there are three definitions. One: authority is “The Man,” a person or institution with power to enforce compliance to rules established by other authorities; two: authority is a person or institution with acknowledged expertise in a particular subject; and three: authority is a knowing that comes from within, when you know what is right for you and you make a commitment to manifest just that, no matter what. To be really successful managing the imprecise zone that characterizes intentional community and the law, we need to know how to identify and work successfully with all three kinds of authority. Sometimes that is not so easy, but always it is an experiment in the laboratory that is your own life.

Consider a few sketches and skeletons from my community’s closet.

“Every Code Started As An Obituary”

Early on in the development of our community at Breitenbush Hot Springs Retreat and Conference Center (near Detroit, Oregon), one of the county inspectors was up looking at some installation we’d just done. He told me, “Every code started as an obituary,” i.e., the laws are there to protect human health and safety, and each code was formulated to address some danger that caused the death of someone some time ago. I pointed out that some codes appear more the result of successful lobbying by interest groups who stand to make a profit, e.g., product manufacturers and contractors. The discussion/debate ended up in the philosophical territory of Spirit vs. Letter of the Law.

Over the more than three decades since that conversation, we, the Breitenbush Community, have engaged in many discussions/debates amongst ourselves, and with authorities, about how to interpret existing laws, how to apply them, and, occasionally, how to seek variance from them. Sometimes you win, sometimes you lose. And sometimes it takes a long time for relevant laws to catch up to what is actually happening in the lives of real people in the real world, when what is happening in that real world represents a better world than what the law allows or limits.

Minimum Wage, or Else

The first few years of Breitenbush was all work and no pay, literally. We had money only for building materials, tools, and permit costs, not for labor, thus the early adopters (people, like me, who joined the community at its inception during the late 1970s) made no money at all in exchange for their work. (You might wonder how workers afforded to eat, and that is an interesting story, but not the subject of this article.) Eventually, we began to pay ourselves $1/day for our labor. After the first year we gave ourselves a raise to $50/month, and slowly our compensation increased for the next few years, up to about $100/month.

But in 1987, we were outed to the Bureau of Labor and Industries. The Breitenbush Co-op was promptly fined $10,000 for exploitation of human labor and ordered to pay Oregon minimum wage, or be shut down by order of the State. We argued that We the Workers were actually We the Owners, and as responsible owners, we were paying ourselves, as willing workers, wages commensurate with our slowly increasing income stream. After all, it takes a long time to build a business. The State responded they could empathize with the dilemma we faced as We the Owners, but that their job was to protect We the Workers, so comply or die.

We lost that battle, but as with every loss, there is a gain. The upside was, overnight, We the Workers suddenly became minimum wage earners. Fortunately for We the Owners, our guests supported the drastic uptick in rates necessary to pay for it all.

The Law Is Illegal; Break It

The ’80s were years of engaged social activism, particularly related to Oregon’s forests. Breitenbush joined the struggle to keep our forests vertical and alive, instead of horizontal and dead. As a private inholding, set deep in the forest, surrounded by millions of acres of public lands, we committed ourselves to two strategies: 1. Educate the public about the abuses happening on their public forestlands; and 2. Oppose the industrialized logging that was laying waste to vast tracts of wilderness. We raised tens of thousands of dollars by direct appeal to our guests to fund a lawsuit against the government, challenging the legality of existing laws, policies, and practices. These practices allowed the US Forest Service to sell multiple units (e.g., 60-acre sections of ancient forest) within the same watershed to bidders who turned these units into massive clearcuts and obscene profits.

Yet the law allowed the public to challenge this carnage in court only on a clearcut-by-clearcut basis, thus protecting industry and government from having to be confronted by, or take responsibility for, the cumulative impacts of all clearcuts in a single watershed. As you may imagine, a single 60-acre clearcut in a large watershed will have miniscule bad effects. But, the cumulative impacts of dozens of 60-acre clearcuts in that same watershed are devastating to soil, plants, riparian zones, water, fish, animals…everything. Our lawsuit contended that cumulative impacts must be recognized and assessed to understand the magnitude of actual outcomes, and that the existing laws, policies, and practices, though “legal,” were in fact illegitimate. As far as we were concerned, the law was worth breaking.

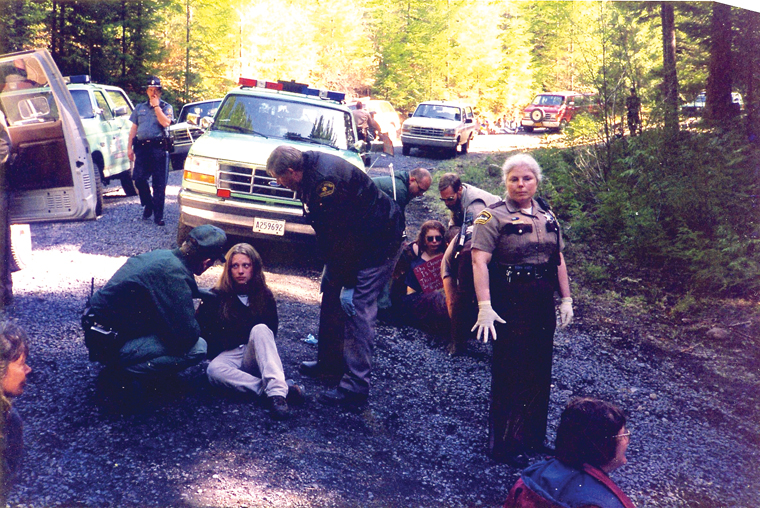

Thus, beyond the lawsuit itself, we made common cause with Earth First! and other environmental protection organizations to engage in civil disobedience, e.g., climbing and occupying trees in logging units, building stone walls across access roads, and other activities. Years passed during which there was a very tense standoff between environmentalists and the US Forest Service, local loggers, and nearby small towns dependent on logging revenues. Law enforcement agencies, the press, and the public all reacted. Meanwhile, we sought counsel from authorities such as professional foresters, wildlife biologists, and attorneys, to understand and sharpen our knowledge of the ecosystem, our place in it, and the legal case.

Eventually, these horrific forest practices were mitigated and peace returned, little by little, to the wilderness. During this period, in order to amend the law, we both broke the law and used the law to change the law. One of the takeaways is that, in addition to finding knowledgeable authorities from “without” (lawyers, foresters, etc.) to change the law by working “within” the system, sometimes it’s necessary to find the authority “within” our own moral code to counter illegitimate authority imposed from “without,” by “The Man.”

But in every heroic story there is an irony, and here’s another takeaway. Sometimes the solution to a seemingly impossible problem comes in a completely unexpected form. It was our strategy to educate the public that in fact led to the key to cessation of logging in these mountains. We figured the best way to educate the public was to get them into the middle of the wilderness, which meant we had to create trail systems deep into those ancient, pathless places for the public to walk and directly experience the power and the magic of nature.

Trail building requires tools, and a lot of work. One of our members refused to use a chainsaw, as he considered that tool to be symbolic of the forest industrialists. Instead, he used a simple bow-saw and pruners. Predictably, he was very slow in creating his part of the trail, so everyone else went out ahead in the forest, building further trail sections. Quietly, he worked until, in one moment, he noticed a family of Spotted Owls peering at him through the lower canopy from a few feet away. They were curious about this calm, slow-moving person and so had come down out of the high canopy to observe, something they never would have done had he wielded a chainsaw.

His discovery of that mated pair (or rather their announcing themselves to him) eventually led to closure of the forests around Breitenbush to future logging operations. This saved thousands of acres from the motorized saw. Such an outcome was only made possible by his simple, Luddite approach to the sacred work of citizenship, plus one of the best laws on any set of books, anywhere in the world, the Endangered Species Act.

“Boiler? I Don’t Got To Show You No Stinkin’ Boiler”

When I got to Breitenbush, there was no electricity, heat, running water, septic system, or communications capacity. We had to build all of that. Between 1977-1981 we worked hard on utilities, which included drilling wells to tap into subsurface geothermal aquifers (hot water) to use for space heating. We first found heat at Well #1 (near the Lodge) and soon began installation of our district heating system by connecting the heat (190º F hot water) through buried pipes leading into and out of the 100 or so buildings of the old resort. It was a huge project for us, requiring several years of drilling wells, digging trenches, laying pipes, collecting and connecting cast-off cast iron radiators, etc.

The only qualitative difference between what we were installing and a conventional district heating system you might find in an apartment complex or government building is that all those old systems had pipes connecting to a boiler in the basement, that heated the water or steam, that heated the radiators in the rooms. We didn’t have a boiler in the basement because, at Breitenbush, the boiler is the local volcano, Mt. Jefferson. Our problem was that building codes for residential/sleeping quarters contain specific requirements for paraphernalia on boilers, such as the Hartford loop (the Hartford Insurance Company of America got tired of paying out for death and destruction based on preventable boiler explosions back in the 1890s—see obituary subtitle above), to make sure boilers and nearby people don’t get blown up.

Having a volcano for a boiler is anything but typical—no near-boiler piping, no Hartford loop, no low-water cutoff, no pressure-reducing valve, no expansion tank, no boiler venting, no mud leg, no BTU output or efficiency ratings printed on the side of the boiler as required by law…nothing. And yet, these are precisely the things that an inspector comes up to inspect. The first time a code inspector came out to inspect our new district heating system and asked to see the boiler, I pointed towards the mountain and said, it’s over there. After a few frustrated attempts to correlate the required paperwork to the existing system, they gave up and approved the heating system and “boiler connection” anyway.

This scene has been replayed several times through the decades and only recently has the county finally written a variance for this code compliance issue. Which just goes to show that a mountain is bigger that a molehill located near a basement boiler, and sometimes a one-size-fits-all law doesn’t fit all applications, after all.

Seeking Variance: Spirit of the Law vs. Letter of the Law

Just because there is a legal definition or requirement doesn’t mean you have to live by it, especially if you live in an unconventional way. And, as I observed in the first paragraph, those of us who live in an intentional community can be anything but conventional. There is the Letter of the Law of course, and duly authorized representatives of county, state, and federal agencies have a duty to engage and enforce compliance. By the way, I respect “The Man,” don’t get me wrong, and always treat representative authorities with honor and kindness. These people have a lot to teach us—but that doesn’t mean they’re right all the time. Letter of the Law advocates often lose sight of the original intent of the law, and will sacrifice the Spirit of the Law without regard for consequences or better outcomes. And that is where individuals and intentional communities have to get creative.

There are many examples I can think of that serve to demonstrate such creativity, but I’ll touch on only a couple here. Obviously, prohibition laws come to mind, and I am reminded of a quote attributed to President Abraham Lincoln that nicely sums it up: “Prohibition…goes beyond the bounds of reason in that it attempts to control a man’s appetite by legislation and makes a crime out of things that are not crimes… A prohibition law strikes a blow at the very principles upon which our government was founded.” Here Lincoln articulates the Spirit of the Law that is shredded by any subsequent law that “makes a crime out of things that are not crimes.”

The War on Drugs has been in effect, one way or another, since long before I was born, with many problematic outcomes for society, not to mention devastating outcomes for millions caught in its trap. I generally consider it a War on People. Thus, in solidarity with Lincoln’s logic, and giving a nod to another 19th Century writing, Henry David Thoreau’s “On the Duty of Civil Disobedience,” I have broken the law a number of times since 1968. And here too I can report vindication. Earlier in this essay I wrote, “And sometimes it takes a long time for relevant laws to catch up to what is actually happening in the lives of real people in the real world.” It took 78 years for prohibition of marijuana to be abolished in our state of Oregon. As Bob Marley said, “It’s just a plant, man!”

Seeking variance to an established law is usually done by “legitimate means,” meaning we must present a case to established authorities, who may rule in favor or against our petition for change. At Breitenbush, we have petitioned numerous times for one kind of variance or another. For example, we asked that Oregon’s Statewide Planning Goals, which designate that rural property be zoned “Timber Conservation,” be set aside in favor of what we held to be a higher use for 40 acres of our land. We followed procedure and asked the authorities, in this case our County Commissioners, to rezone these acres as “Public,” allowing us to eventually develop community housing and geothermally-heated greenhouses, among other uses.

It took years of our community dreaming into it, followed by formal planning, followed by Public Hearings, but finally, by unanimous vote of the three (Republican) Commissioners, we were granted a new Conditional Use Permit with the zoning we sought. When the decision was announced by one of the Commissioners, she stated she was persuaded that our community planning represents a profound and sustainable vision for the future, not just for Breitenbush, but for humanity at large. In this, and virtually all cases in which we have sought variance from established law, what we had to prove was that what we requested was reasonable, and in fact made more sense than what the Letter of the Law limited or allowed.

The essential point here is this: we must start by understanding existing law, and the difference between it and what we’re going for. We must then articulate that difference, and petition the authorities for precisely what we want. Often we can convince those authorities of the merit of our proposal, hence the validity for granting variance. As previously stated, sometimes you win, sometimes you lose—but as Wayne Gretzky, the great ice hockey pro once said, “You miss 100 percent of the shots you don’t take.” So go for it and take a few shots. Gretzky also said, “When you win, say nothing, when you lose, say less.” But I say, when you win, celebrate, when you lose, learn from it and try again. Let’s all keep on keeping on for a better world.

Peter Moore is the Business Director of Breitenbush Hot Springs Retreat and Conference Center. He can be reached at bd [AT] breitenbush.com.

Excerpted from the Fall 2015 edition of Communities (#168), “Community and The Law.”