By Nancy Roth

“How,” I asked myself, as I sat at my desk in the guesthouse at Holy Cross Monastery, “did I get mixed up with these guys?” How did I, not only a female but a wife and mother, end up as part of the staff of a male monastic community in the Episcopal Church? And how did such a sociological anomaly as a monastery happen to be perched on a hill on the west bank of the Hudson River in the middle of the 20th century?

Discovering Monastic Community

The answer to my first question is probably “Marie.” Marie was a high school classmate who had come to our suburban New York town temporarily for her third year of high school. We became friends, and she told me about a place in Maryland where the air was fresh, the surroundings were beautiful and quiet, and the people dedicated themselves to prayer and good works. She told me she had been raised, as an orphan, in a children’s convalescent home run by these people: they were jointly her “mothers.”

When she returned to this utopia she described, I decided to visit her. I was met at the train by a woman in black and white who looked as if she had emerged from the margins of an illuminated medieval manuscript. (Marie’s “mothers” turned out, appropriately, to be nuns.) She welcomed me warmly, took me to my destination, showed me the complexities of the guest house, then left me to myself. How quiet it was! I felt as if I had been plunged into a vast ocean of silence. During my days there, I explored the trails of the adjoining state park, helped the nuns peel peaches for shortcake, and joined them for their frequent chapel services which they called the “daily offices.” I began to relax luxuriantly, leaving behind the stresses of SATs, final exams, and high school research papers.

I would return there from time to time. However, in the meantime, I discovered religious communities closer to home: dotted up and down the Hudson River, across the bridges to Long Island, or north of us in Connecticut or Massachusetts. Today, I continue to find peace and a chance to center myself on my infrequent visits to monastic communities. Buoyed by the warm welcome which is part of their ethos, reminded by the regular worship about the values that I aspire to follow, reassured by the natural beauty that surrounds most monastic campuses, I emerge refreshed, ready to face once again my complex and busy life. And, every time I visit, I say a silent “thank you” to Marie.

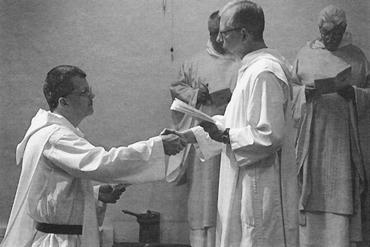

The attraction I had to this way of life—although I must admit my attraction to the handsome organist who became my husband won out easily—eventually helped draw me to this male community when they were at a transition point. I had been asked to direct an Elderhostel—a continuing education program for seniors—by the seminary from which I had just graduated, and happened to be visiting Holy Cross Monastery soon after I had been told by the seminary that they needed to find a site for the program outside of expensive Manhattan. “Would you like to have an Elderhostel here?” I asked Brother Timothy, the guestmaster, one day. He responded with enthusiasm, and, to make a long and happy story short, there ensued more than a half dozen years of creating curriculum, hiring teachers, and welcoming young-at-heart students from near and far. The monastery’s finances became more stable, and they began to have a reputation as a Destination (with a capital D!) in Elderhostel circles and beyond. As for me, I drew ever closer to the brothers and finally was asked to consider being an oblate, which drew me further into the community. I was also asked to become their program coordinator, which enabled me not only to draw on the gifts of my many contacts in the area, but to try out some of my own retreat and workshop ideas, which I eventually offered more widely. Indeed, “Thank you again, Marie.”

Monastic History

The answer to the second question I asked myself in the beginning of this article—“How did such an institution as a monastery come to be in the first place, and why does it still flourish in our era?”—is to give you a brief overview of the history of monasticism. As our son began exploring secular intentional communities, I was reminded constantly of their historical religious communitarian predecessors. There are many parallels. Today’s intentional communities provide an extended family to people who wish to live a life that is an alternative to the present culture: one that reflects their values, not the values of a consumer society. The birth of western monasticism follows a similar pattern.

Originally, Christians who were serious about following the precepts of their religion had often been persecuted or martyred by the Roman emperors who held sway over their world. Then things changed, at the famous moment when the Emperor Constantine won a battle in which he had prayed in desperation to the Christian God for victory and, in profuse gratitude, decided not only to convert to Christianity himself but also to make it the official religion of all his territory. This was not a good thing, in the eyes of the new religion: the subsequent dilution of religious practice so upset many of the more fervent Christians that they decided to flee to the desert, there to live a life untainted by what they considered the sinfulness of the culture. They were quite something: if you want some religious reading that borders on the surreal, yet is full of practical wisdom, read the “sayings” of these first monastics, called the “desert fathers” (although that is not quite accurate, for there were also some “mothers”). At first, these were one-man or one-woman enterprises, but eventually, under a monk named Pachomius, some of them banded together, and communitarian monasticism was born.

Early monastics made vows, often of “poverty, chastity, and obedience.” In other words, they chose not to own anything as individuals, but to hold their property and goods in common, to choose community life over family life, and to put the good of the community first, rather than their own desires, obeying the prior, or head of the community, who represented the idea that each individual was part of the whole.

As monastic communities proliferated, there were variations in the ways that they were organized. (For further information on both past and present-day monastic life, see a book reviewed in Communities #146: Together and Apart, by Sister Ellen Stephen, OSH.) Often this need for organization would culminate in a “rule”: a written declaration of the ways the monks or nuns were expected to live. Present religious communities also have “rules” and, like the very earliest, usually read a chapter of these early every day. If you ever visit a medieval cathedral and wonder at the architectural beauty of the so-called “chapter house” that is usually adjacent, you can picture the monastics gathered on their uncomfortable stone seats, listening attentively (we would hope) to a chapter, most often from the Rule of St. Benedict, who, of all monastics, is best known for systematizing a “rule” that was both spiritually challenging and practical.

People came first, for example. If a monk were at prayer and there was a knock on the monastery gate, he was to interrupt his prayer and go to open the gate! A visitor was to be treated “as Christ.” This is the reason for the myriad retreat opportunities in religious communities today; like the first hospitals into which some of the early communities grew, all monasteries are to be healing places for those who enter. As someone who has often been welcomed in the various communities in which our son has lived, I have often observed—and very much welcomed—this ideal, put into practice in secular communities as well.

The center of monastery life was what Benedict called the opus dei, literally the “work of God,” which took the form of the eight daily “offices” or worship times. There are many ways to connect with that which is beyond us, however we name it—but certainly that same wisdom applies to all who live in community, as well as to everyone else: time needs to be given to nurturing our spirits. Maybe it is through a meditative walk in the woods, or a session of yoga, or chanting in a circle, or sitting in silent meditation. Whatever it is, the opus dei is really the opus of the human spirit too: an activity that helps us to become more fully human, more fully ourselves in every sense, and more connected to reality. And when we sense that we are not alone in that enterprise, but that we are in this together and there is a “Beyond-ness” to life as well, we are fortunate indeed.

Here and Now

It is generally believed that monasticism “saved western civilization.” The monastics protected the great literature of the world in their libraries, continued to sing plainchant, and maintained the priceless frescoes and sculpture. But, more than that, they kept the life of the mind alive, so that the ideas that form civilization were not lost to the barbarian hordes. As I read Communities, I think of this history. Although I know many individuals who are advocates for the planet’s well-being, it is the communities who demonstrate to the rest of the world what it means to live sustainably, both ecologically and socially. Like the earliest monastics who made the vows of “poverty, chastity, and obedience,” present-day individuals have generally had to give up something in order to live in community—the list can include anything from privacy to indoor plumbing! Like St. Pachomius, St. Benedict, and those who gathered around them long ago and, indeed, still follow them, they choose to hold property and/or goods in common, choose community life over life in a nuclear family, and choose to put the good of the community ahead of their own desires. The reward is that the community member is not only a practitioner but also a symbol for others of what Thomas Berry calls the “Great Work” of renewing and rescuing both human society and the planet earth itself. Surely all the saintly predecessors of present-day communities would greet this fact with a mighty “Amen!”

Excerpted from the Spring 2012 edition of Communities (#154), “Spirituality.”