By Andrew Moore

Editor’s Note: In the eyes of some, as Conservative Party Leader for 15 years and Prime Minister from 1979 to 1990, Great Britain’s Margaret Thatcher turned stereotypical gender traits on their head, embodying more masculine-associated qualities than even the most hard-nosed male politicians of her day. Many of the “Iron Lady’s” policies seemed to epitomize right-wing hostility to egalitarian and feminist ideals. Yet in at least one case, she became an unexpected ally to “anarchist, subversive” change-makers working for cooperative housing for the homeless.

Here, a key player shares the inside story…

● ● ●

It was not my idea and I could have spoken against it, but it was the first decision the housing cooperative had taken completely on its own. Inviting Margaret Thatcher to open the cooperative’s first newly built apartment building in North London surprisingly turned out to be a brilliant decision and a game changer for us all.

I and some friends had started a not-for-profit cooperative agency housing homeless people in London. One of our land purchases had been a sizable green field site next to a golf course in the leafy lanes of outer London in the borough of Finchley. As project manager and architect I had played a big part in helping a group of single parents and their children from disparate overcrowded inner city council estates come together to form a cooperative.

It was a bit of social engineering on our part, moving working class families into the heart of Tory land where they would live in and manage this property and support each other in splendid suburbia. I felt I should do everything I could to help them fit it. Having Margaret Thatcher MP for Finchley give her blessing to the project would be a good start.

● ● ●

I had already had several encounters with Mrs. Thatcher and none of them had been very pleasant, hence my reluctance to engage with her again. I especially did not want to give her the opportunity to gain kudos from this housing project when her own policies would never have allowed such a scheme. The cooperative decision had had unanimous member support so I went along with it.

My first encounter with Mrs. T. had been a strange one. It took place when I was 17 years old and still at school. Just as I was mastering the art of subterfuge against anything establishment, to my great surprise the priests and Head Master made me Head Boy at the Catholic Public School I attended in Finchley. I could hardly get out of it as my parents, who were spending a fortune on school fees, considered this a great honour. One of my duties at the end of the year, on prize-giving day, was to give a speech of thanks to the visiting dignitary that gave out the prizes, which were usually great tomes of books describing the lives of the saints. This year the guest of honour was to be the local member for parliament, Margaret Thatcher!

The headmaster told me that it was tradition for the Head Boy not to read his speech but to memorize it. On the night, desperately trying to focus on the few paragraphs I had to deliver to the whole school including the parents, I walked onto the side of the stage at the appointed time. The Head Master was finishing a very long-winded list of his school achievements when I found myself standing next to Margaret Thatcher. She looked me up and down and whispered, “Head Boy, your shoe laces are undone.” I looked down and they were not. “Head Boy, you had better do them up or you will trip,” she insisted.

I bent down to retie my laces just as the Head Master had introduced me over the microphone. I looked up to see the whole hall looking at me quizzically as I appeared to be genuflecting at Margaret Thatcher’s feet. Needless to say, by the time I reached the microphone my speech had completely flown out of my head. Luckily I had written it on a piece of paper in my pocket and after an agonizing few moments I found the speech, read the first line, and the rest came back to me.

● ● ●

The second run-in was a bit more serious. The late 1960s, with the Labour Party in power, saw a swing to economic prosperity and a massive spending on public sector infrastructure projects. Thousands of houses were compulsorily purchased from their owners in the inner boroughs of London so that they could be demolished to make way for school and hospital extensions as well as major road-widening schemes. By the early ’70s unfortunately the economy had suddenly nose-dived and none of the ambitious projects could be afforded any longer. Thousands of handsome five- and six-story stucco Georgian and Edwardian houses were left to rot as there was not even enough money to demolish them.

By this time I was an architect and with some friends had formed an agency to house homeless people in inner London. We saw an amazing opportunity. All we had to do was provide some links and resources to encourage homeless people to occupy all these abandoned empty properties. We wrote The Squatters’ Handbook, a do-it-yourself house repair manual for people who had very little money or building skills.

Whilst my colleagues had written the chapters on how to get the plumbing and electricity working again, I had written a forward which explained how to occupy a property without committing a crime. Squatters were encouraged to tear this page out of the handbook and to pin it to the front door of their newly occupied house. It made the point, just in case the police arrived, that the occupation was not a criminal case but a civil one.

We encouraged everyone to photocopy the handbook as often as they liked and to add any tips to it themselves before passing it on. The Squatters’ Handbook was a huge success and soon took on a life of its own, with many versions in circulation. There were very few challenges, by the property owners and the police, to this early “occupy” movement which enabled thousands of disenfranchised, excluded people living in London to find homes overnight.

It was clear too that many of the municipalities which had purchased these properties in the heady days of a white-hot economy did not now know where the deeds were located. What greatly encouraged the occupiers to secure their position and invest in improving the houses to a high standard was that they had heard by now of an ancient medieval English law. It states that if anyone occupies a property not belonging to them and is not legally challenged for 20 years then the property becomes theirs.

These activities and a copy of the Handbook reached the attention of Margaret Thatcher who was now leader of the opposition in Government. She made a big fuss in the Houses of Parliament: “Did the House know that there were anarchists in the city subverting the course of capitalism by encouraging scroungers and down and outs to occupy some of the best properties in London?”

● ● ●

This explains why Margaret Thatcher was not my first choice to open a unique housing project I had worked very hard to bring to fruition. However I duly sent a formal letter of invitation to Margaret Thatcher MP for Finchley at the Houses of Parliament half hoping that, with only three months to a national election, she would be far too busy. Within a week we received a House of Commons embossed envelope and letterhead with a personal letter from Margaret Thatcher saying that she would be delighted to attend and officially open our housing project.

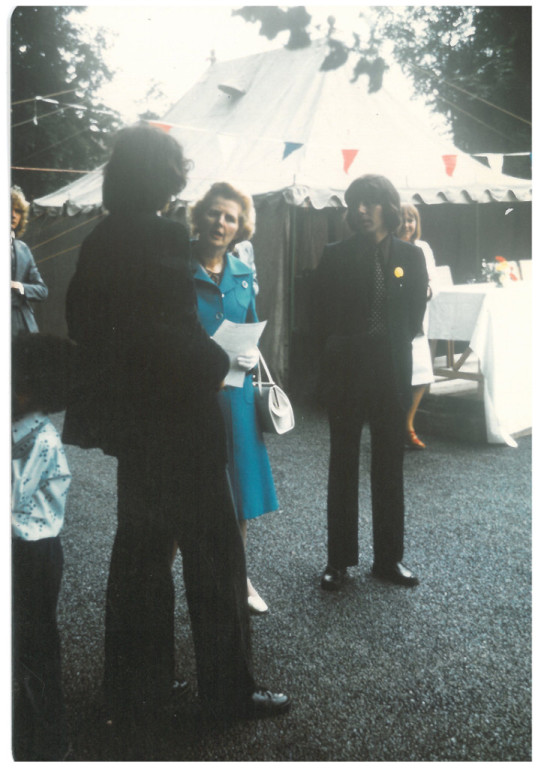

The co-op members were as thrilled as they were anxious, never having been involved in anything like this before. One of the single mothers’ boyfriends said that he would like to be Master of Ceremonies and everyone agreed that they should make an effort to make her feel at home by holding a tea party in the back garden, in a Marquee with bunting. Someone had heard that the Queen normally offered cucumber sandwiches at her garden parties, in triangles with the crusts cut off, so parents and children would make mountains of cucumber sandwiches.

● ● ●

On the appointed day, co-op members and children, friends, and the press were all out in the street eagerly awaiting our guest of honour. There was no sign of the MC, who had earlier gone to the nearest pub for a drink or two to settle his nerves. Nobody was sure what happened to him but he never did make it back that day.

A black chauffeur-driven limousine arrived on time and Margaret Thatcher MP stepped out and waved to everyone. The only person accompanying her was her bodyguard, a plain clothes policeman who pretended to be invisible and unthreatening even though you could see that he had a big bulge under his left arm pit. The limousine pulled away and left her in the middle of the road with a crowd of people gawking at her in a circle around her.

With the MC missing and no backup plan in place, Mrs. Thatcher stood isolated in this crowd. She tried to engage a few people in conversation but everyone was too shy to reply. She looked stranded in her own constituency, unfamiliar with the social ways of the interlopers from inner city streets. The bodyguard was no help as he always kept a steady 10 paces behind her. Every time she walked a few steps the circle followed her but with everyone keeping a safe distance.

Although I had intended to have very little to do with her I could see that an intervention was needed. I jumped into the circle, walked up to our guest, introduced myself as the architect for the project, and invited her to view the apartments and to meet the housing cooperative members. She looked so grateful; clutching my arm, she said that she would love to have a tour. We established an odd relationship; she only ever addressed me as Architect, with me calling her Margaret. She attached herself to me in a way that clearly showed that she was not going to let me out of her sight for the rest of the day.

● ● ●

We did not get off to a promising start. No sooner had I shown her around the first apartment than she started telling the occupier that I had put the kitchen in the wrong place. Maybe this was an attempt to build rapport with the members. She followed this up by saying, “We know about these things, don’t we, ladies?” The mothers, all carrying babies on their hips, nodded in agreement with everything she said. I thought that this was bad manners on her part and decided to go next door to alert the tenants of her imminent arrival. Whilst there I was surprised to hear Margaret calling me from the communal staircase, “Architect, Architect, where are you?” When I caught up with her she almost beseechingly said, “Please stay close to me,” and then by way of explanation, “In case I need to ask you questions.”

During the rest of the tour she was politeness itself and by the time she had visited the last apartment, stroked the last babies under the chin, and complemented the mothers on their choice of décor, she was clearly a convert. She was impressed not just with this project but with the whole cooperative concept. What she most liked about it was that it provided affordable housing without any level of government having to manage the project.

“Marvelous, Architect, splendid—I can see this is a very good way to enable the less well-off to help each other to pull themselves up by their own bootstraps.”

Very surprised at her encouraging words, I led her around to the back of the building where the huge Marquee had been erected with bunting flapping in the breeze. There were over 100 people gathered, taking part in the sunny afternoon tea party. She was quite taken aback. “Architect,” she exclaimed, “where did all these people come from?”

We had been told that we must follow a political protocol. To an event such as this, if you invite someone from one level of government, then you have to invite members from all other levels of government. I thought she would be pleased with the opportunity to jolly along her Party only weeks away from the general election. Perhaps we had overdone it in our eagerness.

“They are all going to want me to promise them the earth, which I will not be able to deliver, even if I become Prime Minister, and then they will be disappointed in me. You had better keep me in conversation so that I will not have to talk to them.” I was already warming to her, particularly after her earlier supportive words. Her confiding tone and irreverence for the established way of doing things was, dare I say it, creating a bond.

● ● ●

I led the way to the cucumber sandwich mountain, filled up our plates, and found a quiet spot at the back of the Marquee. I could see the assembled notaries and press peering into the tent wondering why we were not mingling and socializing.

“As a matter of fact Margaret,” I said, “I did want to pass an idea by you.”

“Go ahead Architect, what is it?”

I explained that the cooperative model could be the answer to the squatting “problem” in London. Despite many complaints by local communities about the dilapidated state of the houses pulling down market values, and much to the delight of the occupiers, nobody had worked out a solution to date.

“Architect, if you can come up with a solution, I and my office will fully support you.”

As a nonprofit organization we could receive the properties in a land transfer possibly free of charge. By now the properties had very little value, particularly if you take into account the expense of evicting everyone, boarding the houses up, and paying a security company to watch them 24 hours a day. Through access to federal Housing Association funding our group could handle the rehabilitation of the properties, bringing them back to their former glory. We could also work with the squatter communities to assist them to transition to long-term rent-paying cooperatives.

She thought that this was a very good idea and that we should go and talk to some of the politicians right now. Clearly her best form of defense was attack.

A high-up official of the Greater London Council was first in her sights.

“Councilor, I want to introduce you to Architect here. He has a splendid solution to your squatting problem.” (She implied that he had created the problem; in fact it had been his Labour predecessor who had gone on a massive municipalisation spree.) “You have far too many properties as it is without taking on the squatter issue; just transfer them over to Architect’s organization and let him get rid of the problem. I can vouch for his good work here in Finchley.”

I had already met the Councilor on several occasions and I was sure he thought of me as a communist. I could see him trying to work out how I had gained the trust of one of the most right-wing members of the Conservative Party. She suggested we make an appointment to meet and that we must report back to her on our progress.

She gave a speech that afternoon in the garden saying how much she had enjoyed herself. She thanked me publicly for explaining the project and the cooperative concept. She said this scheme should become a model for housing the less well-off throughout the country.

After a few more sandwiches and a few more speeches, we said our farewells and she was gone. I never did meet her again.

● ● ●

It took several months to follow up with the Greater London Council meeting. By this time Margaret Thatcher was in office starting an 11-year reign as Prime Minister. The Councilor kept to his word and began transferring hundreds of houses over to us.

This was by no means the largest housing program in the office but it had become the most comprehensive. As project managers we were not only rehabilitating hundreds of houses but effectively we were rehabilitating thousands of squatters into law-abiding tenants and collective landlords of prime property in central London. I often attended their committee meetings to ensure the transformative process was working. Many times we had difficulty reaching a quorum as so many members were out at night classes upgrading their certificates and training to become Yoga teachers, acupuncturists, and school teachers—in fact everything Margaret Thatcher would hope to see: tax-paying members of society.

I often look back on that day and wonder how I had persuaded her to go out on a limb on this controversial squatter program. I have always had a nagging doubt that it had been the other way around. She had recruited me to her worldview and seen me as her agent.

The last time I visited the single-parent cooperative I discovered that the mothers had all joined the Finchley Conservative Party. The Party had more than welcomed them on account of their Margaret Thatcher connection. When I looked a bit shocked, they laughed and explained that they were more likely to meet wealthier men here; men who could presumably keep them in the lifestyle to which they now aspired in their new salubrious suburban surrounding.

Excerpted from the Spring 2014 edition of Communities (#162), “Gender Issues.”