By Jesika Feather

Our community fell together in Waveland, Mississippi, post-Katrina. We all found our separate ways to the New Waveland Café, a relief kitchen started by the Rainbow Family days after the Hurricane ravaged the Gulf Coast. When Rainbow gathering meets disaster zone, over-stimulation is an understatement. The hum of the refrigerator trucks eternally cloud the background. Oddly costumed kitchen volunteers stride here and there with boxes of zucchini, chicken legs, mayonnaise, and tomato sauce.

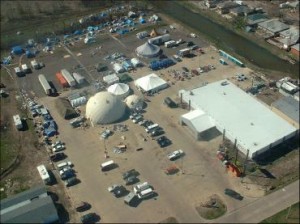

The parking lot where our kitchen was stationed was shared with a distribution center staffed by a church group. Their counters carried everything from evaporated milk and Vienna sausages to fall-themed centerpieces at Thanksgiving. A bird’s eye view would show dreadlocks, mini-skirts, and baggy overalls amiably mingled with gray crew cuts and lime green t-shirts reading, “The Church Has Left the Building.”

We washed dishes, chopped cantaloupe, smoked meat, and sanitized surfaces until the city of Waveland could stand on its own, at least as far as pancakes and pulled pork were concerned.

From there we moved on to St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana, where we started a non-profit, Emergency Communities. Our new relief kitchen, The Made with Love Café and Grill, served an average of 1000 meals a day from December 2005 until June 2006.

We came to know one another over the span of months. Our facility housed thousands of volunteers. Each day was a blur of names and faces. Most volunteers were available for short periods of time (one week to one month). Those of us who couldn’t bring ourselves to leave, developed a ragtag family.

The parking lot of a destroyed horse betting establishment, Off Track Betting, became our home. A geodesic dome, borrowed from a Burning Man camp, became our dining room. Two long rows of port-a-potties actually started to feel normal. Our pantry consisted of a series of refrigerator and freezer trucks along with a large army tent we named Hot Lips. All this was connected by paths made of pallets—to keep our feet from touching the Katrina-poisoned earth.

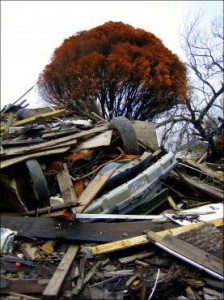

For the first time in our lives, cement was clean. Grass was dirty. In the disaster zone, all laws are changed. At least cement can be bleached. It’s a quick fix, but it will take years for the earth to heal herself.

None of us are from Louisiana. Like all good hippies, we’ve eaten our fair share of beans and rice, but apparently we were naïve to the subtle intricacies of Red Beans and Rice, the way “mama” makes it. For one thing, it’s supposed to be served on Mondays. The locals pushed their way into the kitchen, determined to teach us about Gumbo, Jambalaya, Bread Pudding, and even fried alligator. We swallowed our pride, handed over our spatulas, and took notes.

Though the action at Made with Love centered around the kitchen, many of my current housemates fell into responsibilities that had little to do with food.

Valisa and Benjah took on the job of reigning in the ruckus that occurs when hundreds of homeless locals, rebellious volunteers, and passionate eccentrics reside in tight quarters. Their work was complicated by the ubiquitous presence of “flood liquor.” In essence, Katrina gathered up every liquor bottle in New Orleans and tossed her bounty to the masses. Unopened bottles could be found in trees, streets, and abandoned buildings. Benjah, Valisa, and the other volunteers on security never suffered a boring moment.

Lali, aside from facilitating at least two meals a day, initiated the ritual of “singing the menu.” As the residents of St. Bernard Parish waited for the serving line to open, Lali, followed by a convoy of volunteers, wound her way around the dining room. The dancing procession improvised a rhythmic rendition of the menu. The dome echoed with jubilant calls about ham, potato salad, rolls, and peas.

Brian was our rock. As the months wore us down, our already zany idiosyncrasies became increasingly pronounced. Brian stayed solid through it all. He was generally indispensable in every area. Primarily he headed up the First Aid tent but he also washed dishes, provided technical support, worked security and, most importantly, made sure we all wore sunscreen.

I specialized in breakfast. And, because I have an internal alarm clock, I was also the self-appointed wake-up fairy. I crawled from my tent at 5:30 in the morning, still in my pajamas. I pulled on my muck boots and traipsed from tent to tent, rousing volunteers to begin cracking eggs, lighting the griddle, mixing pancake batter, and chopping apples. I picked out a CD—the soundtrack that would define our morning.

By 6 a.m., the kitchen was a hodgepodge of personalities. No one ever had to wake up, but somebody always did. The volunteers were different every day. Sometimes they were hung-over, sometimes they hadn’t gone to bed yet. Sometimes they were grandmas who effortlessly threw down pancake batter for the masses like it was your average Sunday brunch. Sometimes they were 19-year-old college girls who, when confronted with the prospect of fruit salad for 400, displayed such performance anxiety you’d think they’d never peeled an orange in their lives. Frequently it was gutter punks, conspiring over corned beef hash in a wok—demanding an uncustomary array of spices, swearing “this is how the locals like it!”

Now, when I try to remember us three-and-a-half years ago, it’s as if I’m remembering a dream. Those people—pretending they know how to cook green bean casserole with onion crispies, and then serving it to 700 mouths…those people rushing around at 2 a.m., their tents crushed by the weight of the rain, tarping 300 bags of ginger snaps, wondering if the ovens would work in time to cook the frittata. Those people, with filmy June-in-Louisiana skin. Was that really us?

At the end of June, The Made with Love Café and Grill closed down and Emergency Communities founded three new relief kitchens. Our haphazard group of 10 tired, financially pressed disaster relief volunteers crawled into a VW van, a Toyota truck, a Mercedes with no reverse, and pointed ourselves west.

I still can’t define what held that tentative caravan intact over the year and a month it took before we sat in an office with a notary and a realtor, signing piles of home ownership papers with a Turkey feather quill.

The year that transpired between starting the ignition on our caravan, and hanging Mardi Gras beads in the window of our new home, was a huge transition for all of us. Whether it was conscious or not, that year led to drastic changes for both our communal and individual identities.

Co-owning a house is a huge financial and social commitment. All decisions affecting our home are made by consensus. This ties us to a considerable financial obligation and a lengthy amount of time invested in communication and conflict resolution with our co-owners.

These choices were not made carelessly. We spent eight months meeting weekly to create the legal document that bound us. During this time, several people realized that this was not a decision they were ready to make. Some backed out entirely, others lowered their level of commitment by choosing to be renters rather than owners. By the time we were ready for signatures, there were five of us still committed to owning.

The eight months we spent creating our legal documents could never be defined as a honeymoon. As far as understanding the personality types we were venturing to work with, we bore no false pretenses. However, there is a certain “reality” surrounding our financial commitment that could only set in over time.

When we arrived in Eugene, we were a crew of traveling volunteers. Now we have a mortgage payment, a baby, full-time jobs, a Subaru wagon, and bags of shorn dreadlocks in the garage. You could say our glamor has been a little…tarnished. Truthfully, if something akin to Katrina struck our country now, we’d be hard pressed to donate our time so freely.

We all have different ways of reconciling with our new identities. I beg someone to play with my son so that I can sit in a coffee shop, eat huevos rancheros, and organize my life into paragraphs. Lali bought a second-hand clothing store and assuages her fears of “normalcy” by wearing and designing the most conspicuously striking outfits in Eugene. Benjah smokes cigarettes with homeless men and swaps theories of impending disaster. Valisa slides recklessly after Frisbees and takes lengthy excursions to other countries. Brian…well, to be honest, I’m not really sure if anything ever fazes Brian. But he, as always, nurtures plants and people.

Our financial commitments have had both positive and negative effects on our community. On one hand, we have a contract that gently nudges us back together when we feel inclined to stray. If there were any glaring issues, we could ultimately end it all, but the added complications keep us from making spontaneous or flighty decisions.

It is imperative that we work through any conflicts that arise. We can’t push anything under the rug. We plod our way through agitation about too much dog poop in the yard. We acknowledge fears that some folks get more respect than others, and we hold discussions about whether or not a gun is allowed in the house.

After three years of bi-monthly house meetings and spontaneous breakdowns over sinks full of dishes, confrontation is not nearly the graceless, self-conscious scene it used to be. Now we have a common vocabulary and experiences to draw from. The communication skills we’ve honed while living together have also pulled us through difficult scenarios in our jobs and personal relationships outside this community.

Our financial commitments have also worked against our communal bond. Most of us make the majority of our money by working social services while holding side jobs that involve our other passions. In this way, we manage to serve our larger community while keeping our creative spirits alive. This also means that we work more than 40 hours a week. After prioritizing the nine-to-five job, the art work, the management of art sales, and miscellaneous personal situations, it can be hard to make it home for dinner, much less to attend a house meeting.

It is realistic that after dedicating one year to disaster relief and another year to founding this community, people have to nurture their personal ambitions. If individuals aren’t fulfilled, the community cannot thrive.

It is also clear to me that working through intense experiences to achieve common goals is what gave this community its sticking power. Maybe that’s why, after we’d signed our names, haggled over rooms, and hefted in the piano, I started to get nervous. What would we do with nothing left to work towards? In my mind, the sweet feeling of success was muted by the fear that we’d reached a dead end. I know we can maintain this community through a disaster, but I still wonder if we can stick together through the mundane.

Within days of signing our home-ownership contract, we discovered that I was pregnant. Mostly, I would call this a coincidence. However, I can’t deny that with the end of our home-search in sight, I was zealous for a new community project. The idea of a baby, at least temporarily, absolved those fears. As we all know, it takes a village to raise a child…right? Nine months later, reality set in.

Ash, our baby boy, is currently 13 months old, and we are 13 months wiser. My husband and I learned that the ol’ “it takes a village” routine doesn’t actually apply to the first year of life. Unless the village is so hell-bent on child rearing that they invest in an industrial breast pump and start inducing lactation, the first year is going to belong to the mama. The infant dwells in a very small neighborhood consisting of the left boob and the right boob. He’ll broaden his horizons later.

Only in the last few months has Ash begun to belong to our village as a whole. While every member of this household is undoubtedly invested in his upbringing, a community mission statement this child is not. In fact, for my husband and me, he has been another individual project, diverting our attention from the community.

However, when he pushed his five pound, four ounce body into this world, every member of this community was present to cheer him on, and he knew, from his very first breath, that his support system extends far beyond his father and myself.

Now there are days when my life consists of nothing more world-changing than five loads of laundry folded in increments between playing with my son and baking a pie. Each member of our household wakes up to an individual alarm clock, gazes into a day planner blotchy with appointments, and rushes off to nurture the world, individually. I can’t help but wonder if we aren’t wasting our group potential. While I clean a sink full of eight people’s dishes before making myself a bowl of oatmeal, I can’t help but wonder…what exactly is the point?

On other days I rush to my job, secure in the knowledge that my son is giggling at home with Valisa. Someone else scours my egg pan, and I glide expertly through quibbles with co-workers. Maybe I am getting something out of this.

I have to remind myself that learning to live together does make the world a better place. That raising my child in a household that faces conflict, but hugs afterwards, is a form of disaster relief. That cooking 10 different dishes, simultaneously, in a very small kitchen, and enjoying it, is a community bonding ritual.

In answer to the question, “what does your community do?” I would have to say, we are growing up together. We are inspiring one another to live to our full potential, and we are squeezing every ounce of passion from the mundane. At least, while I fold the 489th diaper, I can giggle at Lali, in the background, clomping her cowboy boots and singing “Hey, mama rock me.”

As I look into the changing faces of my housemates, I remind myself that this is only one of many cycles on our life path. The rich history that binds us is truly a blessing. I should be equally grateful that we’ve been given this time to focus on our individual needs. Hopefully, in the near future, we‘ll find a way to combine our service skills to create a new phenomenon of beauty. Let’s pray that it won’t be prompted by disaster.

For information about current rebuilding projects in New Orleans and St. Bernard Parish: www.stbernardproject.org/v158, lowernine.org.

Excerpted from the Fall 2009 edition of Communities (#144), “Community in Hard Times.”