By Maggie Sullivan

It may seem impossible to create an intentional community inside an existing city with all the difficulties in zoning restrictions, red tape, and political jockeying. However, Dandelion Village successfully navigated the legal hoops to form an ecovillage within the city of Bloomington, Indiana and their success can be replicated elsewhere. Their keys to success were understanding the process, identifying allies in positions of power, and communicating with complete transparency about their goals and plans.

While rural ecovillages can provide better opportunities for farming and connecting with nature, urban locations have their own benefits, like car-free living, sewer systems, public libraries, better school options, a market for goods produced by the ecovillage, and a more vibrant social scene. Danny Weddle, one of the founders of Dandelion Village, dreamed of creating an ecovillage in his college town and gathered a group of five people who were ready to make it happen. “We looked for a property that was 15 minutes from downtown on a bike,” said Danny. Their original vision was of a 50-member community on a permaculture-designed urban farm with members living in small, minimalist cabins and sharing a communal building with the kitchen and bathrooms. This design would allow higher density than typical single family home developments while maintaining much more greenspace and focusing on “hyperlocal food production.”

By scouring the property listings and keeping an eye out for “for sale” signs, they located a potential property just south of town. They held a series of work sessions to produce a 14-page ecovillage development plan. At the same time, Danny, Zach Dwiel, and Carolyn Blank set up casual meetings with a few sympathetic city council members, such as the chair for Bloomington’s Peak Oil Task Force. These city council members were very supportive and had many suggestions on how to navigate the planning process. Their chief advice was to start talking with the city planning department immediately to determine their options and the best approach for obtaining approval.

Like many fast-growing communities, Bloomington has extensive development guidelines geared towards preserving the exceptional quality of life valued by its citizens. Simultaneously ranked as one of the best college towns, one of the best places to retire, and one of the best gay/lesbian communities, its local culture is artsy, diverse, environmentally conscious, and progressive. Happily, the staff at the planning department was intrigued by Dandelion Village. “Many of the goals of this project…are things the city has been dictating and encouraging through the Growth Policies Plan,” said development review manager Pat Shay, commenting on its compact urban form and its use of an otherwise hard-to-develop lot. However, the project was a challenge because it did not meet traditional zoning requirements. “This was a new issue for Bloomington,” said planning director Tom Micuda. “We did not have a code for cohousing and that meant we had to go for rezoning for the land. Essentially we did a PUD.” PUD (Planned Unit Development) was designed mainly for developers looking to do large neighborhood developments and allows developers to propose a layout different from the standard pattern. Generally, the idea is that the city gives some sort of concession to the developer (for example, higher density) that is mitigated by the developer offering some benefit to the city, often in terms of subsidizing additional infrastructure costs or helping the city meet one of its development goals like preserved greenspace.

While things were advancing with the planning department, the Dandelion Village group had less success purchasing a piece of land. The owner of the first property raised his price 20 percent, pushing it beyond their budget. Danny, Zach, and Carolyn continued their search via Google Earth and by bicycle. Another promising property fell through before they stumbled on an unusual location that became their ultimate site. It was an odd piece of land sandwiched between a train track, a trailer park, a cemetery, and the blue collar Waterman neighborhood. After conducting environmental studies to determine that there was no contamination from a nearby salvage yard, they purchased the 2.25 acre property for $57,000 and resumed work on the PUD approval process.

Although the Dandelion group had quietly rallied support for months, their first official presentation was to the Bloomington Plan Commission in March 2011. This 11-member board reviews all proposed site developments within city limits and makes a recommendation to the City Council to grant or deny project approval. As part of the process, neighbors were notified of the project and invited to attend the Plan Commission meeting. “In all my years as planning director, Dandelion Village is the most unique project I’ve ever worked on,” said Tom Micuda. “We also had to work through what I would call the fear of the unknown and the fact that ecovillages and cooperative housing are not within the lexicon of standard plan commission members so we had to educate about what that meant.”

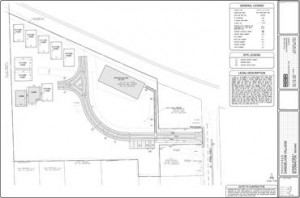

For the first meeting, Danny and the ecovillage group developed site sketches and proposed development layouts. Their initial strategy was to ask for far more than they thought would be approved, which would allow some room for negotiation. They asked for a density of 15 houses and 75 people as well as site exemptions to allow composting toilets, a large chicken flock of 50 hens, a small herd of goats, barns, and only two parking spaces for the entire development with the understanding that the members would live largely car-free.

Several plan commission members were skeptical of the idea and many were concerned about having farm animals near a residential neighborhood. However, they were impressed by the group’s dedication and preparedness and intrigued by the idea of a project countering the “McMansion trend” seen elsewhere in the city. They did advise the Dandelion group that their PUD request would not be approved without plans developed by a licensed engineer. They also listened attentively to the neighborhood residents who came to the meeting and voiced deep concerns. In response, the Dandelion Village group began canvassing door-to-door to talk with their future neighbors and understand their fears.

Most of the concerns revolved around the idea that a hippie commune would bring in drugs and undesirables, not to mention crowing roosters and loose goats eating their peonies. “It was the issue of ‘we’re not familiar with this—what will it do to us?’” said Tom Micuda. Many neighbors were also concerned about the impact on existing problems like lack of neighborhood parking and flooding issues. The neighborhood streets routinely flooded during large storm events and there were concerns that any sort of development in the area would make it worse.

The Dandelion group continued to talk with neighbors and even helped relaunch the Waterman Neighborhood Association. They also incorporated water retention structures into their site design. Instead of causing additional flooding problems, their development was designed to improve the situation by holding back runoff from the adjacent neighborhood to the north. “We approached from a permaculture prespective,” said Danny, describing how they elected to turn waste into a resource. “Water is one of the most critical flows you can possibly have. There has been a drought for the last three years so we said ‘Let’s be selfish and hold that water as much as we possibly can.’”

Hiring a watershed engineer was not cheap but allowed them to present a much more professional set of plans to the Plan Commission at their second hearing. Through the negotiation process, they ended up reducing their density to 30 adults and 10 children with 10 small houses and one large communal building that could contain up to 15 bedrooms as well as a large kitchen and dining hall. They had originally hoped that the small houses could be built without kitchens and bathrooms but that would have classified them as a commercial development (e.g. residence camp) and required the installation of sprinkler systems in all buildings—nearly as expensive as putting in kitchens and bathrooms! They did get permission to have both chickens and goats on the site as well as barns for their agricultural equipment. Composting toilets were abandoned in favor of city sewer connections.

The Plan Commission officially approved their request for a PUD in August 2011. By then, public sentiment was generally in favor of the project and the neighbors who had voiced the strongest opposition began admitting some respect for these crazy young people and their vision. Curiosity replaced concern and the project was unanimously approved by the Bloomington City Council in October as an excellent example of walking the sustainability talk.

By this point, Danny and the other ecovillage founders were worn out but happy. They knew there were still three more permitting steps required and they now had the engineering support needed to develop their final plat for the site. In April 2012, they submitted the final plans for review to get their grading permit, which essentially approves their watershed engineering. Simultaneously, they applied for building permits so that the first two homes could be constructed in the summer. As part of their PUD agreement, they must complete all site grading and basic infrastructure (e.g. storm water retention ponds and main roads) before applying for an occupancy permit, which they hope to acquire in the fall. Once the first founders move in, they will start work on two small community houses and the large community building that will provide a gathering space as well as bedrooms that can be rented out to generate income for the ecovillage and house other members as they build their own permanent homes.

The Dandelion group is thrilled by the location and are excited that they have already formed a bond with their new neighbors. “After a year and a half of politics, it feels great to be through the political process and almost ready to break ground,” says founder Zach Dwiel. “I’m super excited to start building and stop politicking.” While their community has continued to form over potlucks and planning sessions, the members look forward to working side by side building their new home.

Danny acknowledges that this is still the beginning, for both Dandelion Village and for encouraging ecovillage development everywhere. He will be busy for the next couple of years helping the community develop and take ownership of their property. After that, he plans to return to the planning department to propose that their development be used as the model for a new zoning category specifically for ecovillages. “I feel the greatest effect we can have on the ecovillage movement is to set the precedent of a cooperative housing zoning category for the city of Bloomington,” says Danny. He hopes this will pave the way for similar developments in Bloomington and even be adopted in other communities. Perhaps someday his ecovillage zoning category will even become the new normal.

Excerpted from the Fall 2012 edition of Communities (#156), “Ecovillages.”