By Tim Miller

Spirituality can mean a lot of things. It can involve conventional, mainstream American religion; it can involve noninstitutionalized, personal aspirations; it can mean adherence to utterly unconventional (but deeply felt) religious ideas.

American intentional communities of the past have espoused ideas that were both unconventional and fascinating. Here I would like to share a few of the distinctive ideas of three American communities of the past as an exercise in understanding beliefs far out of the mainstream.

Koreshans and the Hollow Earth

One communal spiritual movement that operated from the late 19th to the mid-20th century was the Koreshan Unity, which, after beginnings elsewhere, settled near Fort Myers, Florida, in the 1890s. Cyrus Teed, a physician, had a dramatic revelatory experience in the winter of 1869-1870 in which he believed he was shown all the secrets of the universe. The most fantastic of those secrets was the disclosure that the earth was hollow and that we live on the inside of it. He began to attract followers and he soon gathered them into a community, located first in upstate New York, then in New York City, and finally in Chicago until an attractive tract of Florida land was offered to the group. Teed, in the meantime, took the name Koresh, Hebrew for Cyrus. The biblical Cyrus was something of a messianic figure, so Koresh was a name that suited someone with unusual spiritual insight. The following continued to grow and reached over 200 in the early 20th century. The believers constructed many buildings and cultivated lush gardens in the subtropical Florida climate.

Teed/Koresh had many critics, as one might expect, and he was determined to prove his hollow-earth theory correct. He and his associates created a “rectilineator,” a straight wooden beam installed parallel to the surface of the ocean; extended far enough, they reasoned, it would hit the water as the interior surface of the hollow earth curved upward. And they claimed that it worked, thereby proving the Koreshan theory.

Teed died in 1908, and the community slowly dwindled afterwards, finally closing with the death of the last member in 1982. The land and buildings now comprise the Koreshan State Park. Whatever one might think of Teeds’ ideas, his unusual spiritual community endured, in its various locations, for a century.

Lawsonians and Zig-Zag-and-Swirl

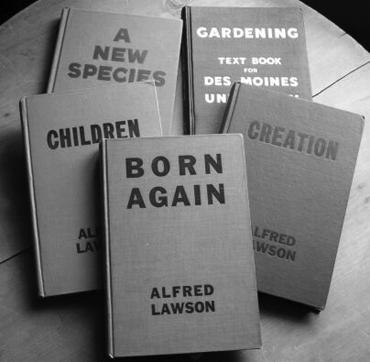

While the Koreshan Unity was entering its slow decline in the 1920s, another visionary arrived on the scene: Alfred W. Lawson, a former professional baseball player and inventor (he claimed to have built the first airplane that could truly be called an airliner), announced that to him had been revealed all the secrets of the universe, universal truths that were somewhat different from those of Teed. Lawson determined that suction and pressure were the forces that governed physical motion, and that penetrability, which meant that one substance could penetrate another, was the foundational law of physics. He also declared that yet another force, zig-zag-and-swirl, further helped explain the phenomenon of motion. Then there was equaeverpoise, which explained the clustering and declustering of matter. Like Teed, Lawson claimed to have figured everything out. He was not modest, to say the least.

The communal phase of Lawson’s program began in 1943, when he purchased, for a song, the campus of the defunct Des Moines University. Renamed the Des Moines University of Lawsonomy, it became the communal home of some of Lawson’s most dedicated followers. The “university’s” curriculum was eccentric, to say the least; it mainly consisted of the memorization of Lawson’s voluminous writings. The student body appears never to have been large, but it was quite fully communal. New students were advised to bring nothing with them, because all would be provided and they would work collectively to support themselves.

A system incorporating all universal truths would naturally involve religion, and Lawson obligingly created one. It was most fully developed at the communal campus in Des Moines, where the chapel became the first church to practice Lawsonianism. Seven other local churches, scattered around the United States, followed by the 1950s. Their services were similar to those of typical Protestant churches, except that they did not have prayer. Lawson’s doctrine was that God was impersonal and did not meddle in human affairs, but rather ran the universe through the fixed laws of nature that Lawson had already identified. Ministers in the local churches read sermons written by Lawson; parishioners sang hymns with familiar tunes but new Lawsonian lyrics. Lawson published a guidebook to the new faith, Lawsonian Religion, in 1949, by which time the world had entered the nuclear era. The new faith provided the insights necessary to prevent the destruction of the human race, Lawson boldly claimed, but only if the world recognized his own messianic role. Few did; by then he was in his declining years and could make little new headway.

Keristans, B-FICs, and Kyrallah

And then some have simply invented their own religions. Kerista was founded by John Presmont, who took the name Brother Jud (for Justice under Democracy), in the early 1960s. Initially, and to some degree throughout its history, Kerista was a movement committed to all-out hedonism, with free love and alteration of consciousness abounding. In 1971 Eve Furchgott joined Jud and friends in establishing a Kerista commune in San Francisco, where a bit of structure was introduced to the freewheeling Sybarites. There they developed a sexual philosophy and practice called polyfidelity, a group marriage, as it were, in which partners were freely shared but members pledged to have sex only with others within the B-FIC, Best Friend Identity Cluster, to which they belonged, and on a fixed schedule, which operated rather like the chore wheels in some intentional communities. They also developed a computer consulting business that made communal life comfortable, even prosperous.

Ever rational, the Keristans decided at one point simply to create their own religion. It was a religion by design; it was a democratic religion, in which doctrines were established by vote. Thus came the concept of Kyrallah, the Keristan name for the Divine, an entity that seeks to emancipate all humans from oppression. Scriptures? Sure, religions need scriptures, so the Keristans wrote their own. The Kerista Theological Seminary oversaw the new religion’s definition of terms, crafting precise meanings for such concepts as religion, spirituality, metaphysics, ethics, and many more. Furchgott, a talented artist known in the community as Even Eve, gave the religion a graphic representation, creating comics that featured the goddess Kerista, a beautiful woman.

Like Lawson, the Keristans sought a comprehensive theory of everything. And for two decades or so it all worked beautifully—commune, religion, business, polyfidelity. In the early 1990s, however, interpersonal disputes arose, and the commune disbanded. With it went one of the most deliberately constructed religions ever.

Bathing Bans, Free Love, and More

Many other communities have stopped short of inventing entirely new religions, but have interpreted traditional religious teachings in decidedly novel ways. The Vermont Pilgrims, for example, an early 19th-century group led by Isaac Bullard, were Christians who did not find any authorization for bathing in the Bible, and as a result were reportedly dirty, louse-ridden, and diseased. The Children of God, now known as the Family, are otherwise conservative Christians who interpret the biblical law of love to mean that free sexual relationships among consenting adults are permissible. Several religious communities have been so averse to private property that they have deeded their land to God.

So what lesson is to be drawn from these unconventional communal spiritual experiments and many others like them? None, really, except that the world of communal spirituality is boundlessly rich and diverse. Communities have attracted some of the world’s foremost minds, and occasionally a few who might be charitably regarded as crackpots. The human spirit goes in a multitude of directions, and community provides a good home for spiritual endeavors of many, many kinds.

Koreshan Unity:

etd.lib.fsu.edu/theses/available/etd-04132010-145407/unrestricted/Adams_K_Thesis_2010.pdf

Lawsonians:

www.humanity-benefactor-foundation.4t.com/index.html

Kerista:

www.kerista.com

Vermont Pilgrims:

sidneyrigdon.com/features/pilgrim1.htm

Children of God/The Family:

www.thefamily.org

Excerpted from the Spring 2012 edition of Communities (#154), “Spirituality.”