By Marianne Wright

Emmy Arnold

June 2020 marks the centenary of the Bruderhof, a Christian communal movement that today is home to around 3000 people of many nationalities living on 26 communities in the United States, Great Britain, Germany, Austria, Australia, Paraguay, and Korea, with small mission outposts elsewhere around the globe. The Bruderhof’s founders were inspired by the teachings of Jesus and the example of the first Christians in Jerusalem, who shared all their possessions. We do the same: Bruderhof members take life vows of poverty and obedience―each of us owns nothing, and we promise to dedicate ourselves to work within the community in whatever capacity we can best contribute. We live like this because we believe that trying to create a society where love and justice are a reality is the best service we can do for our fellow human beings.

Dorly Albertz

My family―my husband Kent and I with our five children―live at Woodcrest, a community of around 300 in New York’s Hudson Valley. (There are smaller communities in cities.) Like other rural Bruderhof communities, Woodcrest has an elementary school, dining hall and community kitchen, medical and dental clinic, community laundry, and income-earning departments. Our family starts the day having breakfast together, joined a couple times a week by single members of the community. We then walk to school or work―I do administrative work for the community school, and Kent is part of the design team for Rifton Equipment, a Bruderhof business that manufactures mobility equipment for the disabled. We meet at noon for lunch in the community dining hall and then go back to work (for the adults) and afternoon activities (for the children). Evenings may be spent having dinner with our family, or―once the kids are in bed―going to a worship or community meeting, joining an all-hands-on-deck project in the factory or garden, or just spending time with neighbors and friends. Daily life at the dozen smaller communities in cities throughout the world is organized differently, although every community meets daily for meals and worship. Some of the city communities run small businesses, while at others people have jobs, volunteer with local charities, or attend college.

Dorothy Mommsen

There are five generations in a hundred years, and my children are fifth generation Bruderhof. Like me, they were born into community life and know the community’s history as their own. They also know that Bruderhof membership is not a birthright: each person, whether or not they grow up here, must choose whether or not to become a member. Communities are made up of individual people, and when our children were born Kent and I chose to name them for people who will, we hope, be a source of inspiration for them as they and their generation come of age. The names of our two daughters reflect the connections between generations.

Our first daughter, Gwen, was born in June 2015 almost exactly a year after the death at age 92 of Gwen Hinde. Grandma Gwen was a tiny woman, untiringly gracious, perceptive, and forthright, and extremely fond of her noisy pet canary Aled Jones. She had lived at the Bruderhof since 1949 when, at the age of 29, she traveled from South Carolina to Paraguay, to which the Bruderhof had fled from Nazi persecution during World War II. In 1959 she married John Hinde, an Englishman who had worked at Lloyds of London before himself making the perilous wartime sea voyage to Paraguay; horrified by wartime suffering, he was looking for “a life that removes the occasion for war.” At the time they joined the community, there were only a handful of elderly people―most members were in their 20s and 30s. By the time John and Gwen moved to Woodcrest in the 1990s, there were a number of older members on each Bruderhof community. Since the Hindes had no children, they were cared for by a succession of younger couples who lived next door to them, helping them with household duties, providing an arm as they walked to communal gatherings, and sharing each other’s company on weekends and in the evening. Living with someone of a different generation is an education (for the young) in the skills that make community life possible: humor, persistence, and humility. “This life is a life of daring,” John liked to say. “It’s the life here itself that is the adventure.”

Erika Wright

Gwen’s second name is Margaret, for Kent’s mother (who has been known all her life by her second name, Erika). At 75, Grandma is incredibly energetic, walking and swimming, baking and canning, and passing on her love of music to her violin students, including Gwen. My guess is that she was named for her grandmother, Gretchen Hildel, a single mother who died a year after the birth of her only child, Rudi. Left an orphan, he was brought to the first Bruderhof community in Germany in the 1920s. He and the other community school children fled Germany in the 1930s when threatened that a Nazi teacher would come to take over the little Bruderhof school. They lived briefly in Liechtenstein and then moved to a farm, the Cotswold Bruderhof, in southern England. It was here, some years later, that Rudi met his future wife Winifred. She cycled to the community from Oxford, where she was an undergraduate, looking for a way of life “worth living and dying for.” Neither Rudi nor Winifred had relatives on the community (hers disowned her when she decided to join, although they later reconciled). The community became their family: as singles, they joined other families for meals, holidays, and weekend activities. When they were married there were hundreds of people to celebrate with them, and later to rejoice in the births of their five daughters, to grieve with them when their son was stillborn, and to share all the other unexpected joys, sorrows, and frustrations of life. And in their turn they provided the same to others with their faithful friendship, generous hospitality, and unmatched ability to entertain―no one could tell an anecdote like Opa Rudi.

Gretchen Hildel

Our second daughter, Dorothy, was named for my grandmother. She and my grandfather came to the first American Bruderhof, Woodcrest, in 1958 with their young family (my dad is their oldest child). Woodcrest had been started a couple years before in response to a wave of interest in communal living among young Americans, many of whom, including my grandfather, spent the war in Civilian Public Service camps as an alternative to military service. (Over a dozen ex-CPSers eventually came to the Bruderhof.) They too believed that war is ultimately caused by the selfishness of an unjust society and they joined the Bruderhof because it offered a real, full-time alternative. Throughout their lives, though, they also found other ways to quietly erode inequality, visiting and corresponding with prison inmates, tutoring children from disadvantaged homes, volunteering in a food bank, and welcoming wayfarers of all kinds into their home.

Our daughter Dorothy was also named in honor of Dorothea “Dorly” Albertz, who lived downstairs from us the summer Dorothy was born. (Bruderhof families generally live in houses with several apartments―each family has their own living space but the kitchen and commons areas are often shared.) Dorly was a kindergarten teacher who came to the Bruderhof during the 1950s as a single woman. She later married George and they had three daughters. That summer of 2018 their house was full of children―ours, their four grandchildren, other small neighbors―who were welcome to come and go, with or without their parents. There were games of Monopoly and roll ball with George, board and card games appropriate for the five- and six-year-old crowd, and a fascinating doll house with tiny china dishes that Dorly had grown up with. She was regal in her reclining chair, happily observing the children spread around the room. With her years of experience as a kindergarten teacher, she guided imaginary play in exciting new directions, adjudicated squabbles, and told stories of her own childhood on a family mill in a little German village. Without ever moralizing, she taught important lessons: fair play, honesty, creativity, how to be a good loser, and, as summer went on and her cancer progressed, courage. She died in October when our Dorothy was four months old.

Gwen Hinde

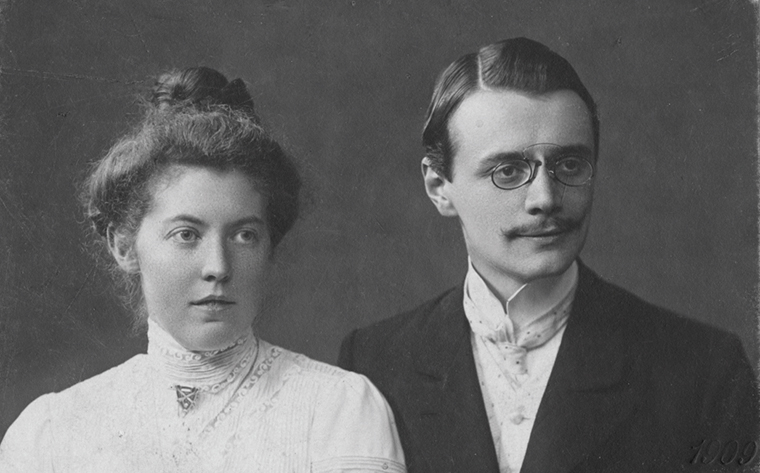

Dorothy’s second name goes right back to the beginning of the Bruderhof―it was also the second name of Emmy Monika Arnold, cofounder of the community along with her husband Eberhard and sister Else von Hollander. Emmy Arnold lived to be 95, faithful to the inspiration which led her and her husband to turn their back on his career as an academic and public speaker, sell their home and life insurance, and move with their five young children to a remote German village to try to put into practice Jesus’ words in the Sermon on the Mount. Eberhard Arnold died unexpectedly in 1935 during surgery for complications to a broken leg, and for her 45 years of widowhood she remained faithful to him. I remember her as a very old person in her lawn chair under the trees; I remember her beautiful smile.

My mother, Emmy’s granddaughter, got the name as well. Mom is an old-fashioned family doctor, which means that I grew up watching her respond to her pager at all hours of the clock, often leaving her eight children in the middle of a meal to suture a cut or treat an asthma attack (my dad was very good at managing the chaos while she was gone). She is still working at the community medical clinic and she still responds to her pager and does house calls, so her grandchildren have her example of unhesitating cheerful service, plus they get a lot of stickers and lollipops from her office.

Monika Mommsen

Our children also have namesakes that are not members of the Bruderhof. Gwen likes to hear about St Gwen of Brittany, known as “saint-bearer” because she was the mother of many saints. It’s hard to be interested in community in the 21st century and not be inspired by Dorothy Day, the founder of the Catholic Worker Movement. And anyone who is interested in how a spiritual heritage can be passed on will look to Augustine’s mother Monika, who famously prayed for her wayward son. There are a lot of St Margarets.

So that’s it. Two girls, four names, and a lot to live up to. There are other names we could have chosen: Sibyl, Ellen, Annemarie, Norann, Nina, Edith, Christel. And if my daughters decide to become the next generation of the Bruderhof, there will be many more names, people who agree with Dorothy Day that the only solution to the “long loneliness…is love and that love comes with community.”

Marianne Wright lives at Woodcrest (www.bruderhof.com/en/where-we-are/united-states/woodcrest), a Bruderhof community in New York’s Hudson Valley. She has edited two books for Plough (www.plough.com), the Bruderhof’s publishing arm: Anni, Letters and Writings of Annemarie Wächter and The Gospel in George MacDonald.

Excerpted from the Winter 2019 edition of Communities (#185), “Passing the Torch: Generational Shifts in Community.”