By Ethan Hughes

Stillwaters Sanctuary, a project of the Possibility Alliance, is an electricity-free, computer-free intentional community located on 110 acres outside La Plata, Missouri. A partner project, the Peace and Permaculture Center, sits on 20 adjoining acres; and another allied group, White Rose Catholic Worker Farm, sits on 30 neighboring acres (both also electricity-free). Here, the group’s cofounder reflects on their choices about technology.

In 1999 I declared to my family and friends that I was going to attempt to live car-free. I was already living without personal computer use, emails, airplanes, and movies. Some of the strongest resistance to this new choice came from my grandmother. She feared a disconnect in our relationship as a result of spending less time together.

My first car-free visit to her home required a half-day of bike and train travel instead of a one-and-a-half-hour drive. The lack of an evening train made it necessary for me to spend the night at her home after our dinner together. Had I still been driving, of course, I would have driven home afterward. Instead we enjoyed a wonderful meal together, played some cards, and stayed up late as she told me stories about my dad (her son), who had passed away when I was 13. In the morning, we breakfasted on the second-story back porch while the birds sang. Suddenly, she reached across the table with tears in her eyes, put her hand on mine, and confessed, “I am so happy you do not drive anymore!” It turns out that I had been the first adult grandson to ever spend the night at her house.

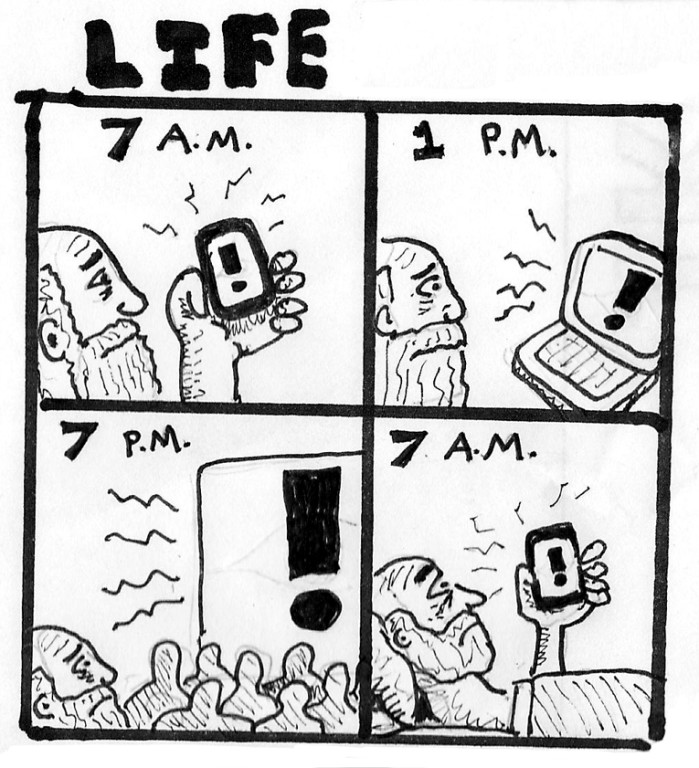

As a result of this and similar experiences, I began to learn that often love is most easily nurtured when we slow down and remove everything that can get in the way of two human beings or a human being and nature interacting. I now believe that movie screens, computer screens, private automobiles, TV screens, cell phones, and other modern technologies simply create a wall between the human-to-human and human-to-nature encounters that can awaken us to love, meaning, and connection.

I also know that another way of living is available to us: a life that emulates the harmonious connection we see in natural ecosystems, a life that lives out the permaculture principles in full integrity. A tree creates zero (unusable) waste, enhances the ecosystem, and supplies a myriad of gifts to hundreds of species. I invite you to believe that humans, you and I, can do the same, that we can shed the trappings of this technological age by conscious choice and once again take our rightful place in the circle of creation.

The Impacts of Modern Technology

Let us evaluate the impacts of modern technology on the earth, creation, society, and our hearts. I believe the greatest conspiracy of our time is the belief that we must kill, enslave, injure, and oppress nature and/or humans to get our needs met. I also invite you to consider that the greater costs of such technology to the living world far outweigh any benefit we may gain from its use. Charles Eisenstein writes: “All of our systems of technology, money, industry and so forth are built from the perception of separation from nature and from each other.”

I propose a movement away from the Age of Information into an Age of Transformation—an age where we are empowered to act on what we have learned and on the calling in our hearts. This great leap and even the thought of it may awaken overwhelming discomfort and turmoil in us. In the face of climate weirding, addiction, species loss, depression, toxicity of the environment, war, and destruction of the last old growth forests, coral reefs, and other climax ecosystems, we must apply an incredible amount of imagination, creativity, love, grace, spirit, and perseverance as we never have before. In fact, to solve such problems, we need a complete paradigm shift.

Some say modern science will catch up and modern technology will become green. It is important to consider that a utopian world through modernization has been promised since the onset of the industrial revolution. In fact, the hard-to-face reality is that no amount of green technology, free energy, or touch screens will heal our disconnection from the natural world; rather they will continue to maintain the barriers that divide us from it. It does not matter if modern technology is clean or has a neutral footprint; it will never bring us back into contact with the earth and universe. We are living in a human-created virtual reality, a technological dreamscape that shelters us from true nature and one another.

As a culture, we are truly frogs in boiling water, indoctrinating each successive generation earlier and earlier into our exponentially accelerating disconnect from nature. According to the New York Times there has been a 69 percent decrease in the time children spend outdoors. This is directly linked to the use of social media, with the average child spending eight hours a day on the computer, watching videos, playing video games, and listening to recorded music. Adults and children are so disconnected from the natural universe that birthed us we do not even consciously miss it. The average American now spends more waking time on a screen than in real life. An infinitesimal amount of people in our society would even consider living with their hands, consuming only what their local bioregion provides. Most could not imagine a full, meaningful life without road trips, stereos, digital music dance parties, coconut, chocolate, movie night, electric lights, and Google searches.

But all of these well-accepted forms of entertainment, communication, and transportation are not as benign as we would wish. In fact, they are cumulatively destroying our planet. Even many mainstream publications now recognize humanity’s disregard of our planet’s natural limits; USA Today recently published an article stating that we are in the sixth mass extinction episode to occur in the five billion year history of planet earth, and that the extinction is human-caused.

In his book The Ascent of Humanity, Charles Eisenstein defines technology as “the power to manipulate the environment.” He goes on to define “progress” as the accumulation of technology. The history of human progress has resulted in our modern industrial society, which Eisenstein states “can remake or destroy our physical environment, control nature’s processes, and transcend nature’s limitations.”

I believe that this kind of progress, essentially an alienation from nature, passed to us through culture, has not only caused the sixth mass extinction and threatened the climate systems of earth but has also jeopardized human beings’ physical, spiritual, mental, and emotional health. Can you truly convince yourself that any of your social media, road trips, imported foods, or documentaries are worth this cost?

Using Technology Appropriately

We find ourselves in a challenging predicament, because the technologies that negatively impact the living earth are the same devices upon which we currently depend for connection, information, livelihood, transportation, food, shelter, clothing, entertainment…almost everything in our lives. How can we do without them? I say we must find another way, for no matter what noble need they fill, no matter what measurable good they create, their use will always keep us disconnected from life in some way. Audre Lorde writes, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” There must be another way to fulfill these needs, or humanity would never have made it to the current era!

This leads us to another important question: Is there such a thing as an appropriate technology? Our definition of appropriate technology at Possibility Alliance’s Stillwaters Sanctuary is:

- It maintains the health and integrity of the biotic and cultural communities it is made in and/or used in. An appropriate technology can enhance the life, vitality, and diversity of these communities.

- All people have equal access to the resources and skills to make the appropriate technology, as well as to use and master it.

- Appropriate technology brings us closer to each other and the ecosystems and species we live with. Appropriate technology promotes relationships with living things.

Here at Stillwaters Sanctuary we live without electricity, use no combustion engines on site, and use no power tools. Even so, almost nothing we use, including most hand tools, beeswax candles, bicycles, and solar cookers, truly meet the criteria of our definition. Yet we know it is indeed possible. Some of us here have visited nearly intact indigenous communities in the Ecuadorian Amazon, islands of Indonesia, and forests of Africa. Almost all their clothing, tools, and shelter qualify under our definition of appropriate technology. We in the modernized world have a great mountain to climb. Skills have not been passed down to us; most of us are not living in our bioregion of birth nor were we taught how to live bioregionally; ecosystems today are more toxic and compromised; and private ownership and widespread division of land make it difficult for modern-day humans to access enough land to live in full self-sustaining relationship with it.

The Computer Reconsidered

If a tool as simple as a brace-and-bit hand drill does not qualify as appropriate technology, how do we begin to assess the impacts of a more complex technology such as a computer? Jerry Mander, in his book In the Absence of the Sacred, proposes a holistic analysis of technology. “The analysis includes political, social, economic, biological, perceptual, informational, epistemological, spiritual impacts; its affect upon children, upon nature, upon power, upon health.”

Let us run the computer through a partial holistic analysis as an example:

● It takes 500 pounds of fossil fuels, 47 pounds of chemicals, and 1.5 tons of water to manufacture one computer (in a world where one third of the human population does not have access to clean drinking water).

● 93 percent of the global population does not own a computer and of the poorest one billion, only one percent has access to one.

● The US military is the #1 financial source for computer science research in the world.

● 70 percent of the heavy metals in landfills come from e-waste.

● Paper waste has increased 40 percent with the spread of the personal computer and printer.

● The highest number of Superfund sites (extremely polluted locations) in the US are in Silicon Valley, where computers are manufactured.

● Computer-run systems are cheaper than hiring people, so more money is concentrated in corporate hands, unemployment increases, and the poverty gap widens.

● Computers increase surveillance, used for concentration of power and control by corporations and governments.

● The manufacture of one computer chip contaminates 2,800 gallons of water.

● More than 700 materials and chemicals are used to make a computer. One half of these are known to be hazardous to ecological and human health.

● The entire process from raw materials to the computer in your hands requires minimally 200,000 miles of transportation (almost to the moon) with resources extracted from up to 50 countries.

● Simply by the process of its production, a computer is the antithesis of decentralization and bioregionalism.

● Each year between five and seven million tons of e-waste is created. (The majority of this is sent to China, India, South Asia, and Pakistan.)

● The people who build our computers have up to 3,000 times the rate of certain cancers. These workers also have a much higher rate of respiratory diseases, birth defects, miscarriages, and kidney and liver damage.

● 70 percent of all people affected by e-waste (lead, phosphorus, barium, dioxins, furans, etc.) are poor and marginalized people.

● 40 percent of all computers on the planet are owned and operated in the United States.

● Computers are efficient at accelerating consumption, development, advertisement, etc.

● The main Google server in the Columbia River Gorge uses more electricity in one day than the City of San Francisco.

● The computer is a product built for profit. The industry’s imperative is growth and profit.

● The computer is rearranging our brain chemistry and functions, in addition to creating psychological patterns of addiction to its use.

● 90 percent of human communication is nonverbal. Thus we use only 10 percent or less of a person’s capacity to communicate when we do so through computers.

This is less than five percent of the information on the negative impacts of computers that I have collected in the last decade and a half. Please do your own analysis and research and let me know if you find new or differing information. As Jerry Mander urged us, I am focusing on the negatives in our holistic analysis. We all are familiar with the benefits―they are why many choose to use the computer.

The simple fact that we can exist without a computer seems like an impossibility these days, yet for 100,000 years we have—we did so even just 50 years ago! Wendell Berry quips that “If the use of a computer is a new idea, then a newer idea is not to use one.”

Shaking Our Addiction

How can we change our habits, and shake our virtual addiction to modern technology? First we must truly understand, see, and feel the painful costs of the disconnected choices we have made. Bruce Ecker states, “Change occurs through direct experiences of the symptom, not from cognitive insights. Cognitive insight follows from (rather than leads and produces) such experiences.” Whenever I meet people who are living electricity-free, not flying, biking everywhere, sharing their home with the homeless, refusing to use the computer, eating locally, giving their money away, or fearlessly risking arrest for a cause, I ask them what led to these choices. Their answers share two common aspects:

- They came into direct contact with some form of destruction caused by their lifestyle choices—for example, they witnessed mountaintop removal, met brain-damaged Latino children living downstream from Silicon Valley, visited Black Mesa on the Navajo Reservation and saw the destruction caused by Peabody Coal, or witnessed families tenting on the Mississippi in zero degree weather.

- The exposure was sometimes less than an hour, yet all of these people said their lives changed instantly from the direct experience. There was no thought in the decision to change their lifestyles; it arose naturally from their being.

So this is the good news. When directly exposed to suffering, humans will most often respond and take great risks of which they would not otherwise think themselves capable. I myself began experiencing these shifts when I lost my father to a drunken driver. At age 13 I directly experienced the cost of cars and alcohol. All the facts in the world—like this one: the leading cause of death in the US for 18-25-year-olds is car crashes—would not have changed my behavior or choices. Yet one direct experience of the cost of these things led me to live car-free and substance-free. I also stood on the banks of the Aguarico River in the Ecuadorian rainforest as more oil than spilled from the Exxon Valdez rushed downstream, covering everything. Since witnessing that event, I strive to live without depending on petroleum.

I invite you to go expose yourself to a direct experience of the cost of your lifestyle choices. Let the truth of what you see transform you. For example, go witness the dumping of the elephant-sized amount of toxins, contaminated water, and waste created for your laptop. Visit the poor, marginalized town or village that has to deal with it. What if you visited the Superfund site downstream from Silicon Valley and met children with brain damage from computer industry waste? Could you make the same decisions?

This is not a loaded question. It is an honest question I ask myself if I am imagining a truly just world, with equality and opportunity for all life. I acknowledge that it is also very challenging and difficult. When I recently asked a friend to consider doing his world-impacting, beautiful, personal growth work without the computer or airplane, he said he would be “ripped to shreds.” I know from my own experience that such feelings of devastation are real and necessary, and I believe we are called to cross this threshold in order to heal ourselves and this earth. We must be ripped to shreds to enter a new paradigm.

Making the Transition

We have very imperfectly begun the transition back to the living world at Stillwaters Sanctuary, at its neighboring Peace and Permaculture Center, and on the adventures of the Bicycling Superheroes, three projects of the Possibility Alliance. We are constantly learning how to embody our individual and collective vision. We have observed during the course of our 7-1/2-year-old experiment at Stillwaters Sanctuary that people must have time, space, love, compassion, inspiration, and support to transition and integrate a new way of being. Heartbreak, grief, tears, joy, disappointment, despair, laughter, gratitude, grace, and fear have been part of each of our transformations. There is also hypocrisy, paradox, and failure daily.

Just in this moment, for example, I realize that what I write by candlelight with pencil on scrap paper someone will soon type into a computer. What can we do? We are not an island of purity. We choose to interface daily with the society that each of us was born and raised in, and of which we are still a part, albeit a dissident part. This interface involves compromise, but we don’t want to use this rationale to console ourselves into passivity. Step by imperfect step, we must keep marching toward the goal of transformation—of ourselves, and in tiny increments, of that same society. For example, our last newsletter at Stillwaters Sanctuary was hand-drawn and photocopied. One step we’re taking is to commit to print our next newsletter on an antique printing press, as did our friends at La Borie Noble in France, and as did Plain magazine, which printed 5,000 copies each run using typesetting and woodblocks!

With every choice—even if it’s to write an article for a magazine or be interviewed for a podcast—we are trying to create a culture and container where it is easier to live without industrial society. One successful paradigm shift has come from our choice to burn hand-dipped beeswax candles as our only light source at night. Not only do we create a way to have lighting using resources within a 10-mile radius, but we instantly make obsolete nuclear, coal, wind, solar, or any other industrial power source that requires mining, resource extraction, and the old industrial paradigm to create. Our use of candles also makes us more mindful, both in movement and activity. We must move carefully when using an open flame. We reap the gifts of beauty, calmness, human connection, and connection to nature. What began as an environmental choice has become a spiritual one. Living this way brings us closer to the world: bees, hands, fire, spirit, and life.

Although we celebrate any movement that lessens impact to life, we do not consider “green technology” to be the “end all, be all.” For example, shifting from coal power to solar power is a meaningful step, but it may not be enough. As Bill McKibben pointed out in an Orion article, hybrid cars, fair trade goods, wind power, and trains only slow down the process of destruction; they do not end it. Our transition must be an unceasing journey toward a fully healed relationship with the Earth.

Lanza del Vasto offers a gauge to know when we have reached the goal: “Find the shortest, simplest way between the earth, the hands, and the mouth. Don’t put anything in between—no money, no heavy machinery. Then you know at once what are the true needs and what are fantasies. When you have to sweat to satisfy your needs, you soon know whether or not it’s worth your while. But if it’s someone else’s sweat, there is no end to our needs. We need cigarettes, beer, cars, soft drinks, appliances, electronic devices, and on and on…. Learn to do without…. Learn how to celebrate…prepare the feast from what your own hands have grown and let it be magnificent.”

As I continue to simplify and align my life with creation and nature, I am discovering a true and deep wealth: having very little, being happy within the limits of a non-industrial life, remembering that “joy is not in things, it is in us.” Joy is also in connecting with each other and nature with nothing in between. No inanimate thing is needed for the human experience of love, justice, equality, joy, aliveness, and meaning.

This change in my own life has taken 30 years of transition and integration…step by step I am moving toward the goal of living, creating, and enjoying in a way that takes care of and honors everyone and every living thing. My experience with life is increasingly more direct: walking to the orchard composting toilet in a snow storm or under shooting stars; sitting face to face with friends and strangers night after night by candlelight; creating music; storytelling; collecting wild foods; listening to the silence and cricket song that come when there are no combustion machines, no canned music, no white noise; slowing down. In the age of industrial technology it has become a radical act to be completely present with the person or lifeform you are with, with no screens, distractions, intoxicants, or anything else in between.

Many of our friends in communities and projects around the US are shutting off the electricity, shifting to the gift economy, closing email and Facebook accounts. The Downstream Project in Virginia, Be the Change Project in Reno, Loving Earth Sanctuary in California are just a few. This article is an invitation for whoever feels the calling to begin to unplug and plug into What-Is-Alive. We at the Possibility Alliance want to try to support any who would walk this path, by sharing any insights, skills, or resources we have. Let us access more fully the oldest and ultimate technology: community, love, nonviolence, and spirit. It may just blow our minds and hearts wide open.

Ethan Hughes enjoys watching dragonflies, luna moths, and the wonder in the eyes of his two young daughters. He has a long-standing love affair with Gandhian nonviolence and enjoys puddle fights, board games, and jumping into any body of water. He has gotten arrested with nuns three times to resist the war machine (police seem to be much more polite to you when you are with a nun).

Excerpted from the Winter 2014 edition of Communities (#165), “Technology: Friend or Foe?”