By Yana Ludwig

By Yana Ludwig

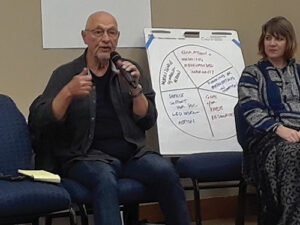

I’m sitting in a Lutheran summer camp conference room on a steamy night in North Carolina, listening to Bob Zellner speak. Everyone in the room is white, and for once, that feels just fine to me.

Bob is talking about his days shadowing Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., being mentored by him and Rosa Parks. Bob is talking about the choice he made that didn’t feel like a choice but a moral imperative, to become one of the first white people to show up in the civil rights movement in the South, joining and helping to nurture SNCC (the now legendary Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee). He is talking about fear, and persistence. And how he thinks now is worse than the ’60s in terms of government repression. Sitting relaxed with a mic in front of the room, Bob talks about his hope for white people organizing other white people to stand up to racial repression, and I can see how his warrior spirit is both sobering for the people in the room, and helping strengthen our resolve to live up to that hope.

In my mind, Bob is talking community, almost from word one. But I usually do that translation in my head when someone is talking about a powerful movement. For me, organizing has shifted over the years from list making and task assignments, to something deeply relational: the authentic pursuit of getting our needs met collectively…a.k.a. community.

I don’t usually expect that translation to be matched by the world around me. So I feel an unexpected thrill when Bob’s language turns in that direction and we find ourselves talking about the power of organizing our lives in order to be in a better position to organize for our lives.

We are now talking about Fannie Lou Hamer, who organized the Freedom Farm Cooperative, a community in Wisconsin of fellow Black folks, in 1969. She is one of the main inspirations of the most exciting thing happening in the communities movement as far as I can tell: Cooperation Jackson.

Except if you go to Cooperation Jackson’s website, it doesn’t look much like a community’s website. I recommended to a communalist conference organizer recently that he reach out to them, and he emailed back a little confused because he couldn’t find the community part on their website. But it is there, woven into the talk of liberation and cooperative economics.

Cooperation Jackson is a firmly Southern project, grounded in the civil rights movement, and grounded in the new economy paradigm that is resisting capitalism on the ground by organizing co-ops, planting community gardens, and yes, starting an intentional community. The richness of these carefully crafted layers of Cooperation Jackson is part of what thrills me. This isn’t organizing a residential community to play the middle class acquisition game more effectively, nor is it community for the sake of simply having a safer place to raise your kids or the leisure time to garden (both of which are fine things in and of themselves, but don’t address systemic issues for others). This is about fundamentally disrupting the systems of economic and racial supremacy in our lives that are killing most of us by inches.

Networks and organizing are powerful for me today in ways that I didn’t find them powerful 10 years ago. Ten years ago, I associated networking with things like the Green Drinks movement: fun rituals, but kinda lightweight in terms of the political power and disruptive potential they have. They were, for me, a way of playing the professionals’ game better, and I’ve always thought that was a game with more downsides to winning it than upsides. They certainly didn’t have much to do with my vision for a transformed society.

Today, networks have really different resonance for me. Both Cooperation Jackson and Bob Zellner have had something to do with that change. (I strongly suspect that my shift in this has been a shift away from the mental patterns of whiteness and middle classness that I’ve been steeped in from a young age. But that is another article, waiting to be written.)

● ● ●

Rewind in my own timeline to the summer before.

I’m in one of those beautiful old big church buildings in downtown Los Angeles, facilitating a meeting of about 25 people. It’s a delightfully diverse bunch this time: old activists and young ones, mostly people of color, and the strongest, most clear voices in the room are from a couple of young women of color doing bold public banking organizing in the city.

The container for this meeting is being held by Commonomics USA, the economic justice organization I am the Executive Director of at this time. But I’m not here as an expert on the topic: I’m here as a facilitator, putting into play the skills I’ve learned in residential community to attempt something that is still cutting-edge in the activist world: deliberately ending silos of interests to make something powerful happen.

This is the first in a series of meetings in California bringing together public banking advocates with fossil fuel and big banking divestment folks. We’ve deliberately invited people who don’t normally end up at the same meetings, including, in this case, public housing activists who see some hope for public banking as a tool, in spite of the movement’s history. The public banking world has been a largely white and upper middle class field for a long time, and to say it has some cluelessness about most people’s actual lives would be kind. But the collective gathered here is interested in changing that.

I’m here in part because there are some really interesting parallels for me between that world and the intentional communities world. Each is centered on its own, very powerful tool: in the one case, publicly and democratically controlled finance; in the other, residential community with all its psychological, financial, and ecological benefits. Both tools can be used, and have been, to maintain and expand the comfort of the already comfortable, and to empower some truly awful things in the world.

The best recent example of this with public banking was Standing Rock. North Dakota sports the only public bank in the US currently, and it has provided a lot of economic resilience to that state. That’s the good side. The bad side is that it was weaponized during the Standing Rock resistance to corporate power, and was a very effective tool to empower the police to shut down the protests.

And in the communities movement, we see communities that use the tool of residential community for a kind of deliberate insularity that allows child abuse, sexism, and other forms of abuse to flourish. I have multiple friends who were raised in genuine cults (a word I don’t use lightly and use only in alignment with FIC’s understanding of what that means). The damage these groups can cause their members and especially the young people raised in them is huge.

The parallel here is this: without a social justice orientation and understanding, both public banking and intentional community can be dangerous and counterproductive to the world we ultimately want to create. However, the flip side is true as well (and the communities movement will benefit from understanding this about itself): used within a social justice framework, community is an incredibly powerful tool for good, and one I am seeing increasingly as being powerful for disrupting systems of racial, class, and other forms of oppression.

● ● ●

Back to that room in L.A. The organizing that happened at that meeting and in the follow-up sessions was one piece of a large, concentrated campaign that recently resulted in a major shift in how the state of California (which is the fifth largest economy in the world) is viewing public banking: not just as a way to continue being a powerful economy within capitalism, but also becoming a force of truly meeting marginalized people’s needs. And we did our best in that meeting to center the voices of young people of color and make sure their agendas were the ones we were pushing the state to take seriously.

This, too, is community: the authentic pursuit of getting our needs met collectively. That spirit, of making our community organizing about real needs (and particularly the real needs of traditionally marginalized people) is what my broader networking and organizing work is teaching me and encouraging me to bring back to what I consider to be my “home” organizing scene of the intentional communities movement.

I want us to become a more powerful movement (a true movement) meeting the needs of people like me: queer, working class, with invisible disabilities in a female body. And I have learned that we will get there only by becoming a true movement to meet the authentic needs of people who are not like me: people of color, trans people, the truly poor, immigrants, and people with much more obvious and impactful disabilities than I deal with.

In short, our networks have to be things that connect the liberation of the white working class with people of color, as SNCC did. They have to connect community, agriculture, and black liberation together, as Cooperation Jackson does. And they have to use every tool we have available to us to connect the dots between finance, law, and liberation, the way that Commonomics is doing.

What the communities movement has to offer these broader movements are hard-won skills in cooperation, facilitation, etc. and the greater ease that comes from living with others and having energy freed up to also be activists and not just survive. What the movements and networks of liberation have to offer us is the ability to see community as a tool of either oppression or powerful organizing for liberation, and to get us solidly on the right side of history: transforming our movement into something that truly can create a world that works for everyone.

Yana Ludwig is a cooperative culture pioneer, intentional communities advocate, and anti-oppression activist. She is a cofounder of the Solidarity Collective in Laramie, Wyoming, an FIC Board member, and a Chapter Coach for SURJ (Showing Up for Racial Justice) which allowed her to meet Bob Zellner. Yana is the author of Together Resilient: Building Community in the Age of Climate Disruption (under the name Ma’ikwe Ludwig), and has been a trainer and consultant for the communities movement since 2005. Yana now offers training on race and class oppression for communities with her partners, Crystal Byrd Farmer and Matt Stannard. See www.YanaLudwig.net.

Excerpted from the Fall 2018 edition of Communities (#180), “Networking Communities.”